1986

If '85 was the arrival of games as a true fixture of the household, then '86 was the arrival of something about games.

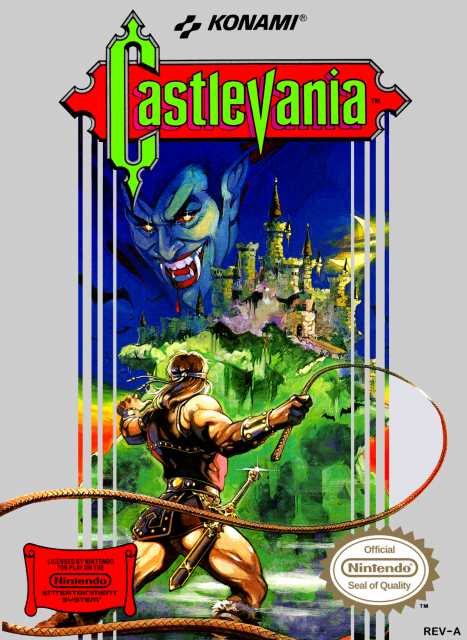

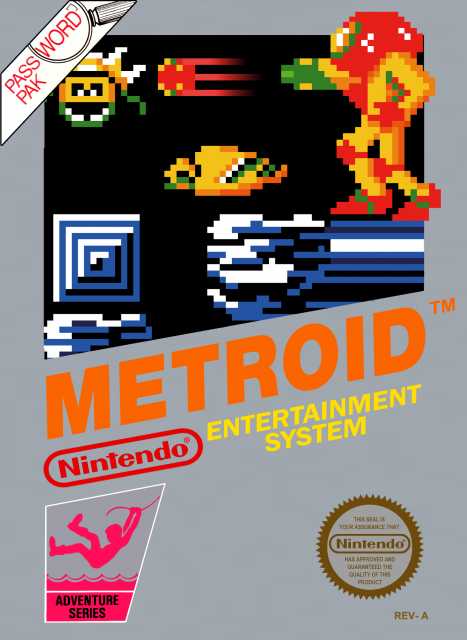

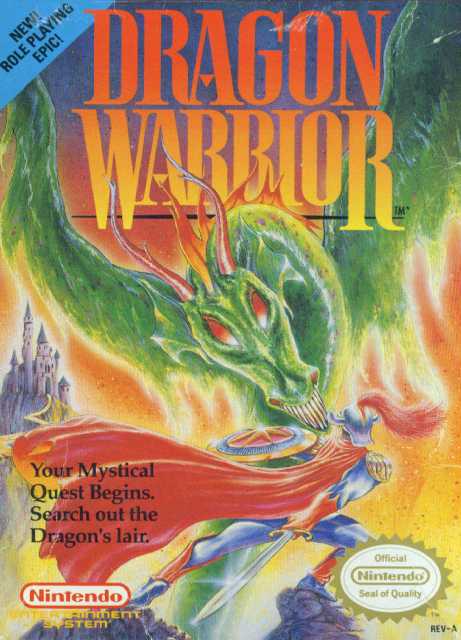

Every game is a journey in some respect. They elapse and change over an uncertain amount of time and take someone with them. However, my favorite games of '86 almost all exhibit how it feels to adventure. That they span a large castle, the bowels of an alien planet, or entire continents are of course important, but even more important is that they investigate how their space communicates with the player over time.

To say that a game's pleasures primarily stem from progressing seems redundant, but the means of journeying, of moving through an environment and everything that comes with it is what I love best about these titles. These games are so present, so in their moment, that they're refreshing even today, when many games often pester you about things that have happened and especially what's going to happen next.

'86 was the year that the voyage mattered.