Weekly Flounder: Conventional Morality Systems

By TheFlamingo352 13 Comments

Welcome back to my weekly attempts at being a decent writer, where I’m trying to get some beginner games-analysis under my belt, one idea at a time, when I nab the time. This week, I'm talking a bit about morality as a game system over the last decade, and why morality bars aren't quite so bad.

This is gonna age me a bit, here- The first role-playing game I ever owned was Bioware’s Knights of the Old Republic (2003). My gaming days before that were primarily filled with my favorite trequels (?), Heroes of Might & Magic III and Civilization III, games that do have RPG *elements* from hero progression to the more literal role-playing as a nation, but that aren’t conventionally loped into the RPG genre. Neither focus on characters’ morality bars or intricate dialogue systems or heavily character-driven stories. Now that’s not to say one can’t play Civ with an eye on ethics, or dive into the emotional drive behind why Catherine Gryphonheart is murdering throngs of Troglodytes. What I can say is that one can’t not interact with ethics and characters’ ambitions in a game like KotOR, where the game mechanics intrinsically affect and are affected by players’ moral decision making.

Those who’ve spoken with me about game design know that I place extreme stress on the importance of game systems and mechanics above all else; art design should be influenced by and work in concert with mechanics; story and writing should be derived from and inspired by mechanics; game mechanics- the core ways by which players interact with games, from character locomotion to leveling systems- are the axle from which a holistic design is built. With morality in gaming, though, there comes a bit of a snag. Quality game systems are clear to the player, allow for intuitive learning and mastery, and operate within the confines of what the player has been taught (or are being taught). Morality is rarely this precise.

This problem has been addressed when Bioware’s Star Wars epic is discussed these days: A meter of numerical values is a poorly simple method of representing a character’s ethical bend. In reality, too, the problem has been addressed in many developers’ games of the past decade, such as Bioware’s own novel solution in their follow-up space opera, Mass Effect (2007). Here, players’ morality is set by the highly crafted narrative of Commander Shepherd; player agency is instead diverted to how Shepherd operates to achieve preset goals. Paragon for a pure hero, Renegade for a violent operator.

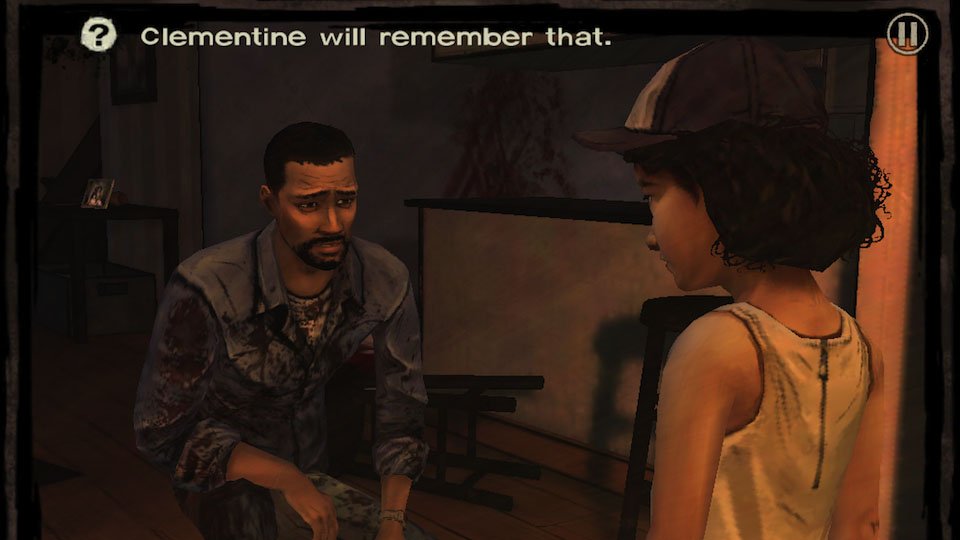

Fast forward another five years to Telltale’s episodic first season of The Walking Dead (2012), where morality systems were completely eschewed in favor of a greater focus on characters’ relationships, as well as how player character Lee’s actions are viewed by other people. What makes this system so interesting is that, since KotOR in 2003, game systems have been steadily backing away from detailing morality as a set code of guidelines, what’s evil and what’s not. This understanding- that in reality ethics are a lens by which actions are judged by other people, not a preeminent law ordaining what can and can’t be done- feels like the most substantial evolution of ethics in gaming in my (admittedly short) lifetime. And yet in spite of this, I get the feeling that something isn’t quite right.

That feeling derives from a dichotomy of thought I have over the evolution of morality systems: specifically, that by improving morality in games, developers are removing morality systems, and for some reason this is bothering me. I suppose the feeling isn’t entirely dissimilar from the upsetting realization that a faulty component of one’s work shouldn’t be fixed, but scrapped in its entirety. It’s the feeling of a loss that is more than warranted, but is a loss all the same.

Or maybe loss is the wrong word. More like a decline in popularity, an obsolescence. So why are morality bars harder to find today? The answer probably comes back to (surprise!) the significance of game mechanics. Stories that want to run realistically, in shades of grey and emotionally moral choices, simply do not come out of games with morality bars. Yes, there are examples to counter this belief- KotOR’s own sequel dealt heavily in the relatively rare neutrality of the Star Wars universe- but these games likely implemented to morally abstract problems purposely to contrast with simple ‘Lightside meters,’ not support or emphasize them.

All that word-junk above is why more modern games with highly polar morality systems like Infamous can get a bad rap**, why line graphs from one to evil are a bit of a joke in the industry. Yes, defining Good as “blue” is a dumb way to signify the nuances behind why player characters perform their allotted actions. But dumb can most certainly also be fun, and I know giving homeless people money for more blue Good points in order to improve this dope Master Heal power is a hilariously fun experience. Maybe then, morality bars get a bad rap not because they make roleplaying unrealistic or trivial, but because poor implementation of this system can fail to do what the morality bar does best: make role-playing fun.

**this is debatable, of course; an exploration of any modern concept of a "good" conventional morality system would have to be relegated to future posts due to time-constraints, unfortunately