Innovation of the Week: The Difficulty Curve

By alianger 1 Comments

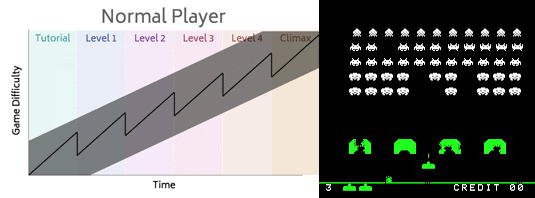

One of the most significant, yet often overlooked aspects of retro gaming is the innovation of the difficulty curve. The difficulty curve can be visualized in a 2D graph and refers to the gradual increase (or decrease) in challenge level as the player(s) progresses through a game. It keeps players engaged and ensures a sense of progression and accomplishment as they overcome increasingly tougher obstacles. Developers generally want to keep players in a "flow" state where they're always engaged, outside of both the frustration and boredom zones, above and below the curve respectively.

Now, while a more or less even difficulty curve with subtle tutorialization of new elements is generally seen as good design today, it can also feel predictable and therefore a bit boring. For some genres, or more complex games or game elements, tutorialization simply has to be explicit. Some games make the early game harder, which can be seen as a narrative tool, creating a sense of (extrinsic) progression and serving the role of creating a power fantasy. Like I mentioned in the risk/reward article, that mechanic blends into the topic of difficulty balancing. If the optional rewards aren't that hard to get, the risk isn't that high and/or the reward is permanent, the difficulty curve can eventually become flattened or even flipped as the game goes on. Various RPGs and Action Adventure games implement this to some extent, with optional grinding, side quests or dungeons that reward the player (often with stat boosts) via leveling, items or equipment. Yet another approach, relating to puzzle games but also other genres, is to insert mandatory and esoteric puzzles or secrets into a game and leave it up to players to try every possible solution (brute forcing) or ask other players to proceed. A euphemistic description is to call this a social element, relying on the audience asking each other how they figured something out and hopefully getting a useful response, which in the best scenario leads to an increasingly obvious hint and the player sitting on the knowledge feeling a sense of pride or that they're needed, and in the worst to just being told what to do (even worse, by a guide rather than in person) and the puzzle being pointless. Then there are rogue-likes and -lites, which tend to throw the expected out the window, have a sometimes wildly uneven difficulty curve and frequently maximize the punishment for failure, which can be very exciting for some players, but very frustrating for other players. Let's have a look at the early evolution of this fundamental aspect of video games!

The first example I can find of a game with a difficulty curve is from the pivotal Pong (1972), and it's about as back to basics as it gets. As the game goes on, the ball simply moves faster and faster. This style is replicated in various later games such as Pac-Man, where the ghosts become both faster and more aggressive, and Tetris.

dnd (1975) - I keep coming back to this game, don't I? In this pioneering dungeon crawler RPG, the curve is intimately tied to risk/reward as the current difficulty is based on how much gold the player's avatar is carrying. Gold can be dropped to quickly lower the difficulty on the fly, or the carry capacity can be increased if the player finds a Bags of Holding item. Tough enemy encounters can also appear, offering to let the player live if they give up their gold, magic items as well as half their experience points. It's a pretty interesting mechanic which sadly wasn't implemented later on as far as I know, at least not within the time period we're working with here.

Space Invaders (1978) - This pioneering shoot 'em up features a difficulty curve that goes back down at the beginning of each new level. This is sometimes called "Nishikado motion" as an homage to the developer, and it was influential (directly or indirectly) on many later level-based action games, where the difficulty generally goes down relative to how far into the game the player is. Some examples are Donkey Kong, Gradius, Mega Man 2, Quackshot, Doom and Warcraft II, but there are many more. You're generally not going to get ambushed by a group of enemies or encounter a hard to avoid, instant death trap right at the start of a level in these games. The pattern seen in the picture has of course also been applied within levels, sometimes multiple times, by giving players a break via a power-up - this can then also get more nuanced with a risk/reward element to acquiring the power-up, something I'll get back to later.

Kid Icarus (1986) - A Nintendo developed action platformer with Action Adventure and RPG elements, it's also known for its unusual difficulty curve, which is initially inverse. The first world/set of sub levels is seen as one of the hardest, consisting mostly of vertical platform levels where falling down means instant death (and just ducking on the wrong platform leads to falling), helping items are very expensive and basic mechanics like how to level up your HP and AP aren't fully explained. Players who do figure it out generally grind a health level or two in the first sub level (1-1) in preparation for the rest of the game, after which the game has a fairly standard difficulty curve besides the winter themed levels, and a few other testing segments where thieves can steal your weapons or wizards turn you into a defenseless walking eggplant. To be fair, the game's difficulty curve makes more sense when seen through an AA or ARPG lense: Metroid and Zelda feature very similar elements and their open-endedness can lead to a lot of early deaths since you are also at your weakest starting out, but they also do a better job at both explaining themselves (via the manuals) and easing the player into them.

Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988) and Zelda: A Link to the Past (1991) - These two are often acknowledged as an early gold standard for the even, balanced difficulty curve, where there's a seamless progression of complexity or reflex-based challenges and new elements are subtly tutorialized for the player. New mechanics, power-ups and enemies are gradually introduced and generally in a more safe environment where the player can experiment and learn by doing. Zelda's difficulty curve can also be extensively tweaked by the player, which brings us to the next category...

The customizable curve (The Legend of Zelda series, Metroid series, Final Fantasy series, Phantasy Star series, Yoshi's Island (and to a lesser extent, SMW), the Fallout series, etc.) - This comes in four (or more?) different types. As mentioned before: If the reward isn't that hard to get, the risk isn't that high and/or the reward is permanent, the difficulty curve can become flattened or even flipped as the game goes on. In the first type, common in RPGs and Action Adventure games, the reward for more time spent and/or taking on higher challenges is a permanent decrease in the overall difficulty curve, or at least a decent chunk of the curve ahead of the player. One Action Adventure example is Zelda: A Link to the Past with its hidden HP and MP upgrades, fairy fountains that offer various upgrades, and making it voluntary for the player to increase their HP after beating a boss.

The second type works like this: beating the main game is a low or perhaps a decent challenge, but the real challenge comes from the optional 100% completion, or a set of tough challenges that the player can take on for a sense of accomplishment and/or actual mastery of the game. In Super Metroid, for example, to get everything or to get the best completion time, skillful use of the Shinespark ability is a requirement.

The third type of customization generally happens before the game starts, via the options menu, and it's generally not a dynamic element. However, a few retro examples of the latter do exist such as Fallout 1-2 and Baldur's Gate 1-2.

Pay to win/Microtransactions (Xybots (1987), Dynamite Duke (1989)) - This lovely innovation and the fourth type of customizable curve, kind of deserves a scathing article by itself. Players were thankfully spared from it to a large degree in the era defined as retro on this site, as it only appeared in the arcades. To be fair, a lot of arcade games incentivized this behavior with a combination of instant respawning after dying or using a continue, and cheap, trial & error heavy difficulty. These two games took it a step further however, by letting players buy in-game currency with quarters (which are then used to buy various items), or buy the items themselves, respectively. There is a limit at 25 credits in Xybots, but this is where this seems to have started in video games.

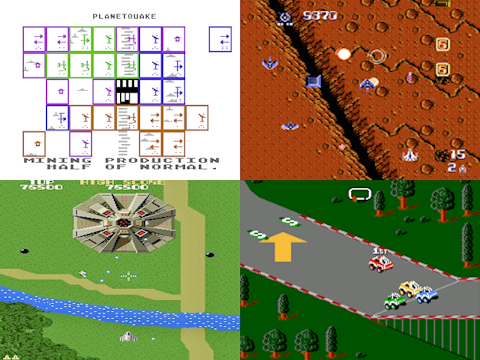

Dynamic difficulty balancing/Adaptive enemy AI/Rubberbanding (Astrosmash (1981), Xevious (1983), M.U.L.E./MULE (1983), Archon (1983), Zanac (1986), Ghouls 'n Ghosts (1988), BattleTech: The Crescent Hawk's Inception (PC, 1988), Little Ninja Brothers (1989)(Easy mode), Dragon Spirit: The New Legend (NES, 1989), R.C. Pro-AM II (1992), Battle Garegga (1996/1998), etc.) - As a form of dynamic difficulty balancing, shoot 'em ups started implementing (often hidden) rank systems in their games as an additional layer of challenge, requiring players to deliberately either play worse, destroy certain targets (Xevious) or sacrifice extra lives at certain points in a game to lower the difficulty to a more reasonable level. Or simply deal with the much higher difficulty level. In Zanac, based on factors such as weapon power, how many enemies have been killed and fr how long you've stayed alive, and more, the game will make the enemies faster and more aggressive. Variants on the mechanic can be found in other games as well: In MULE, where random events are adjusted so that the player in first place is never lucky and the last-place player is never unlucky. In Ghouls 'n Ghosts, the 8 DIP switch difficulty settings determine how hard the game gets the longer you stay alive and how much the difficulty drops when losing a life (there are 16 internal settings in all). In Archon, the computer opponent slowly adapts over time to help players defeat it. How nice!

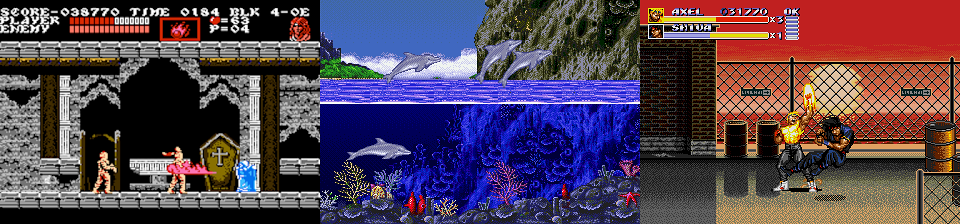

The steep difficulty curve (Bomberman/Dynablaster/Atomic Punk (ARC, 1991), Ecco the Dolphin (1992), Splatterhouse 3 (1993), Umihara Kawase (1994), Gunner's Heaven/Rapid Reload (1995), G-Darius (1997/1998), etc.) - The game generally starts out relatively tough and for the most part only gets tougher. In the case of Splatterhouse 3, this applies more strongly if you are trying to go for a better ending which is based on time taken. In the case of Gunner's Heaven and G-Darius, the curve gets steep after 1-2 levels. Which might make them candidates for...

...The weekend rental showstopper (Castlevania III (NES), Ninja Gaiden 3 (NES), Ecco the Dolphin, Rocket Knight Adventures (E/U), Contra III and Hard Corps (E/U), The Lion King, Dynamite Headdy (E/U), Streets of Rage 3 (E/U), etc.) - While for a lot of earlier games we can only speculate why that particular platforming segment or boss was such a difficulty spike for us, developers have occasionally admitted to creating these intentionally so as to make customers buy the game rather than just renting it. In some other cases, The Cutting Room floor have covered difficulty changes during localization in detail (in Ecco's case, it was made easier for the Japanese localization but also made easier in the later Sega CD release).

The Post-Game (In Lunar 2: Eternal Blue (1994/1998), Lufia II (1995), Diablo (1996), Diablo II (2000)) - Optional challenges eventually started turning into games where getting through the game once is simply the beginning, and a big chunk or even the majority of the game is found in the harder modes, unlocked side quests and in finding all the rare items. Within the scope of this article we're not quite at that point though. In the first Diablo, this consists of replaying the game with the same character on Nightmare or Hell difficulty (it's also possible to do this at level 1 in single player, which initially causes a steep, inverse curve), encounter the rest of the single player side quests (which are randomly selected from a pool), and focusing on player killing in MP, where the reward is an ear marked with the killed player's name and level. In Lunar 2: Eternal Blue, after beating the final boss, players can revisit previous areas, discover several new areas, as well as tie up the loose ends of the story in a satisfying way.

What games do you think have the most interesting or perfectly balanced difficulty curves, and why? Let's discuss and reminisce!