The (As It Were) Cinematic Aspirations of Virgina

THE (AS IT WERE) CINEMATIC ASPIRATIONS OF VIRGINIA

There are games that tell a story and games that have a story, with the difference being more important the more you consider it; a difference between obedient listening and participation in a story, and reckless collaboration between player and programmer. Virginia is thoroughly the former, telling a complex, multi-layered narrative to you that is crafted and considered. You might enjoy the narrative Virginia shows you but any player looking to shape or interact with the narrative will be sorely disappointed and the comparisons to a cinematic experience may prove to be more apt than first thought. You will watch a story unfold in Virginia but you will only watch it - never really interacting with it. You will not play more than Virginia thinks you should play. Virginia is an interesting experience, and certainly not to everyone’s tastes, and while some may find a heartfelt story with dark and interesting themes, others will find a deliberately confusing, openly vague pseudo-game that plays pretend at a being a movie.

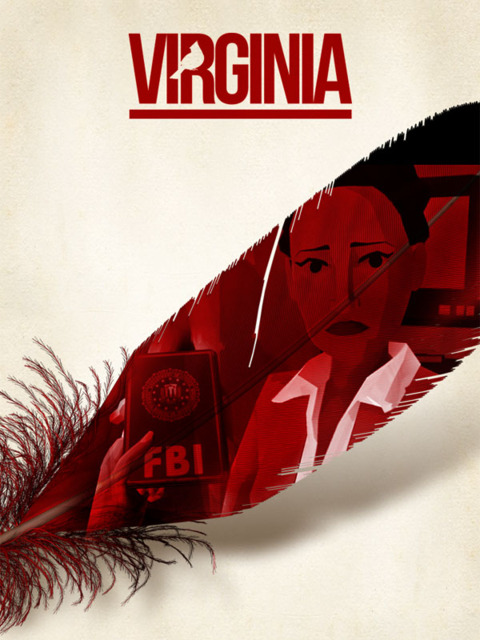

Our time and place is the early 1990’s, Washington D.C. You're a rookie agent in the FBI; Anne Tarvers, still wet behind the ears and your boss puts you on an investigation with detective Maria Halperin to investigate a boy’s disappearance in the town of Kingdom, Virginia. You’re not just paired with Maria by the Bureau’s random decision making - you’re actually watching her for an internal affairs investigation, keeping an eye on Maria while pretending to be her friend. Maria Halperin works in a basement in the FBI like a certain Fox Mulder used to back in 1992, sent down there because of something her mother did. You’re trying to work your way up the chain at the Bureau, hoping to impress your superiors. This is just you climbing the ladder, one rung at time, right?

But over time, it’s clear you’re becoming friends and your motivations begin to become hazy. Complications arise, the stakes grow and the question is who do you trust: your new friend, the Bureau or yourself? Can you even trust what you see? Shifting perspectives, dream sequences, reality fragments and curves it on itself – if Virginia’s inspiration was David Lynch then the inspiration was most certainly Mulholland Drive or Twin Peaks. What’s most impressive about Virginia to me is that it manages to tell all of this – if what “this” is, this assumption I’m making of the narrative, is actually the story – without a single word of dialogue. We see potential futures, dreams, visions, all without a line of dialogue. Everything told to you now, above and below, is inferred through facial expressions, files and the use of editing.

To tell the story in the moment-to-moment, Virginia uses techniques more commonly found in cinema; rapid cutting, match-cuts, montage, Kuleshov effects (whereby a viewer assumes a meaning between two different shots) and things that would feel right at home on a screen. Instead of showing us an entire walk down to Maria’s basement, or even letting us walk the entire way down, we see it fragmented in a montage. We match cut from objects into new scenes, often with symbolic sub-textual reasons. The editing in Virginia, a term not often applied to games, is fast and judicious, holding just long enough to create meaning but pulling away quickly to avoid slowing the pace. It means the game moves quickly through things that it doesn’t need you to overthink on and allows time for bigger moments.

This often works to Virginia’s advantage but often works to its disadvantage too – there are moments when I wanted to read something or attempt to do something but the game moved ahead, barrelling on-wards. I was reading files or papers before cutting into a new scene and had no time to read a single word before the narrative jumped into the next scene. There’s a bonding scene between Maria and Anne that I feel moves a bit too quickly, with them going from acquaintances to good friends in the space of about 30 seconds – I actually wanted to see just a bit more, if only for the sake of character development.

These decisions to omit large chunks of story and detail stuck out to me in particular because there are multiple moments where the game will just let you wander around a house or a room for as long as you want when there is only one thing you can do: interact with a single object to progress the story. There’s a few scenes in Maria’s office and I spent a while trying to find some story related objects to make me connect with Maria; like what does she read? What does she keep on her desk? But that’s not what this scene is about: this scene is about clicking the single object required to progress the story along. You’ll try and interact with radios and lights and computers but there’s no point – there is only the object. The singular object. The object may be a door, or a file or a necklace but it will always be the only thing you can interact with in the room, the invisible button that allows you to make the story move forward. The player’s role at times is like someone clicking the next scene button on a DVD remote to advance the story.

However whatever story there is can be at times incomprehensible and not in the sort of pseudo-confusing way that an arthouse film might be, with multiple interpretations. The game is a blurry mess of half-questions, poorly formed symbolism and by the final act of the game, Virginia seems more concerned with reaching a pointless crescendo that actually making a point; making noise and music for the sake of an ending. And I’m not someone who wants to be told what happened, I adore a good mystery, but I did want a bit more than nothing at all. All the things you might suppose a game to have in it with inspirations like The X-Files and Twin Peaks are in here (I’ll leave that to your imagination), but how it works in any of those things just bewilders me. Virginia chugs along with a story about a missing boy and an internal affairs investigation but then, ten minutes from the end, veers off into a dark wood of completely unrelated things that don’t even make sense in the internal logic of the story or in the external player logic. It’s not so much narrative ambiguity or mystery but rather feels like the video game equivalent of throwing things at a wall to see what sticks.

***

Visually speaking, art style grabbed me; reminding me of games like Thirty Flights of Loving (which Virginia actually calls out by name in the end credits as an inspiration), Firewatch, Sunset and others in that minimalist sort of style. The lighting in particular looks great, with light shafts carrying dust motes and harsh orange sunsets creating long expanses of shadow. There’s an odd shimmer at times to surfaces, presumably a characteristic of the art style, where surface textures sort of blob and move like paint. Characters convey emotion through simplified facial expressions reminiscent of an Xbox 360 Avatar (I swear it’s the eyes, look at the eyes) and are well stylised and proportioned. I loved the art style and I wish the game had done more with it at times through subversion and alteration to create unease or connections with characters. But then again, you don't have any chance to interact with anyone in this game.

What shares center stage with the art style is the soundtrack, a beautifully lush and orchestral soundtrack by the Prague Philharmonic (the creators of Virginia must like David Lynch an awful lot because the Philharmonic scored Mulholland Drive). It’s quite sublime at times, perfectly underscoring moments of tension, sadness and anger but sometimes get a little too bombastic for what I think would be a moment of reserved tension. There’s a moment in a bar where I feel like Virginia is literally screaming to the audience to recognise where its creative inspirations came from, as a band with a red-dress clad woman plays a jangly guitar song that I was certain was so close to Angelo Badalamenti’s guitar laden Twin Peaks score that it bordered on copyright infringement. I understand wanting to call out your heroes but it’d probably be cheaper to just call David Lynch rather than making a game.

***

So Virginia has style. It has a narrative flair, a great look, a beautiful score. It’s stylised, yes, usually going for a less is more design; in fact those words could probably summarise most of Virginia. And while Virginia may be cinematic, Lynchian, stylish and stylised to the nth degree, beautifully scored by an amazing, if somewhat unfitting at times, orchestral backing, what it lacks is player interaction. If you aren’t concerned with that, go buy it. I won’t stop you but read on and maybe I can explain myself further.

There are a category of games that some people – I don’t know who personally but they exist, I’ve seen them online – call “walking simulators”, usually as a derogative insult; all you do is walk, hold forward and the game tells you a story. Then that’s it. These games are often pricey for their short length, pseudo-intellectual and have aspirations of being taken very seriously. After games like Dear Esther, Gone Home and The Stanley Parable codified the genre (minimal interaction, story over substance (unless the story is the substance), usually artistically stylised, quite serious subject matter, etc. et al), dubbing a game a “walking simulator” usually divides a discussion; price vs. value, gameplay vs. story, more battles spring up inside these battles. Recent games like Firewatch, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture and Sunset continue to divide some and conquer others; I can appreciate a story in a game, I really can, but I love it more when the story and the gameplay synchronize perfectly. Understanding how the mechanics of a game reflect the themes of your story is important to me; understanding how the character you play within the story must be allowed to act as vessel within the story. Telling me a story while I walk doesn’t impress me, not any more. The lustre has gone. I don’t want to be told a story while stumbling around an environment - it’s the equivalent of an audio tour of an art gallery.

And I get it. I do really get it, okay. This looks like story-telling or a mature narrative and when you compare it to loads of other video games, it stands head-and-shoulders above “shoot the terrorists” or “solve this block puzzle” plot devices. It reveals a narrative to the play through interaction, however slight this is interaction is. There are two buttons involved in the playing of Virginia: W to walk forward and Right Mouse Button to interact. In fact, you can use Left Mouse Button to walk as well so you could use only your right hand to play and get your left hand free to do whatever you think it might need to do - I used my left hand to rest my chin on, to keep my head propped up.

Story/gameplay synchronization is difficult; it’s such a minute understanding of your narrative, in-game world and gameplay that there’s really few games I can think of that do it well. Thief: The Dark Project does it perfectly - you’re stealthy, silent but also quite weak and you have to resort to shadows, sewers and forgotten passages. The hallways echo with your footsteps, the wind howls through empty passages and Garrett’s quipping helps to alleviate tension. You’re often under prepared, under equipped and woefully outmatched; everything can kill you in a simple hit or two but you need to explore every level to find gold, jewels and treasure to make your money. To succeed you must put Garrett/yourself in harm’s way – you need to sneak past guards and hide bodies and play the role of a master thief/burglar to make things easier for yourself. It is not cinematic or film-like but it is engaging: you have so many options available to you as a player that the agency always lies with you. Every decision you make puts you into the next situation; things do not just happen, you MAKE them happen and that is the focal point of any good story. The player is a driving force in the story, their action makes the story possible and without them, through action or inaction, the story simply would not exist.

***

Thief blends gameplay and story perfectly; Virginia fails to make the two meet at all. There’s such a large disconnect between the player interaction with the story, the actual input of action and the narrative itself, that it’s almost shocking. It’s almost like the player shouldn’t be present at the keyboard at all – as if interaction with the narrative were a last-minute decision by the game designers. The story of Virginia is given to you through your input, certainly you push it forward but your pushes are small and silent.

Supposedly this lack of gameplay is in service of a mature narrative, Virginia is telling a mature story that has the game press buzzing about cinematic story-telling in games; the only comparison most can make are to movies and television, saying that Virginia approaches true cinematic aspirations by its similarity to the works of David Lynch and the television show The X-Files. Mature, cinematic, film-like; these three words are floating around all Virginia discussion.

There are other deeper questions too: how do we communicate a complex narrative when there is a player standing in the wings, waiting to come on? Maybe games can be mature when they start to take themselves seriously (or if being silly and fun, taking their fun seriously) and tell a story that requires a game to properly tell it; a story that allows for interaction with it, for a change to happen because of player input, that does not tell a story to a player but allows the player to reveal a story. Virginia is certainly a mature story, just one that doesn’t require a player to be there. It's akin to Dungeons and Dragons - a dungeon master can write the best story in the world but unless they gives the players a chance to act within it and upon it, and accounts for their actions within the story, they will find themselves in dire straits soon enough.

Making a game is difficult work from what I understand, all the hours coding and designing and scripting and whatnot, and I wonder if the time spent developing a game with minimal-to-zero interaction could be better spent making a movie or a short film. If you wrote down the amount of interaction the player has on a sheet of paper and their interaction is only ‘walk’ and ‘click a button’, I’d probably just make a movie. Virginia is cinematic, sure, but I don’t want to keep comparing games to cinema – that reeks of a sort of cultural cringe. It’s like we’re ashamed of video games, ashamed of the immaturity around them and the fact they don’t command the same critical and artistic value (or integrity?) like films or books do. Even the comparison of Virginia being Lynchian is meaningless – the term Lynch-esque or Lynchian is something that links the game to cinema and is a word that has lost all weight in the past few years, as it seems to be the go-to word for “weird” when the words “magic realism” would seem more fitting. The only thing Lynchian about this is the whole lifting of elements that codified Twin Peaks and slightly off-kilter Americana; both things that David Lynch didn’t exactly invent.

***

Games are games, and this is not even a stubbornness to accept a new type of game like a “walking simulator” or such – it’s that we have a medium where interactivity is its strength, where immersion has never been higher or more present and instead the medium makers aspire to be like something that already exists. Games are an entirely unique and still entirely misunderstood genre - we still haven't explored the full potential of video games. I don’t want to compare games to movies because a game is not a movie; a game is a game and a game has qualities that designate, signpost it, as a game. This doesn’t challenge the notion of what a “game” is because the bare minimum is here. This is a experience that could have easily been a student film or a DVD menu game.

Virginia’s story is interesting, certainly engaging in places but I spent the majority of my two-hour experience with it holding a button, watching events unfold like a film. I walked away from the game with a feeling of apathy; I just sort of shrugged and went “Yeah, okay then”. There’s nothing to say about it – I can’t vouch for the gameplay because there is so little. The story cannot be vouched for because I didn’t think it told itself well enough, despite the developer’s insistence that narrative ambiguity is a substitute for any sort of cohesion in a story. The cinematic aspects? Oddly utilised and while fascinating and interesting in the context of a game, it fails to hide or support the poorly told story.

Aside from the soundtrack and visuals, which are excellent, I have so little to say in Virginia’s favour that it almost feels unfair or mean to write any of this. To walk away so nonplussed and unmoved by a game deliberately trying to impress me and move me feels like something went wrong – either on my end or their end and I’m willing to say it’s a bit of both. Coming at cross-purposes perhaps; wrong day, wrong time.

Narrative is difficult to work with at the best of times – managing characters, motivations, plot threads, etc. Video games have a lot to work through as a comparatively young medium and we’re constantly figuring things out like controls, multiplayer, AI etc. I want a great story-driven game, I really do, but I don’t want to be told a story or even just shown it. This is an interactive medium and I expect a minimum level of interactivity.

This sort of “click-to-progress-the-story” just feels old hat now. I want to be a part of it - driving the story forward myself, just knowing that my being there in the story is important and necessary, even in moments of weakness and failure. That my actions and inactions are a driving force, that things happen because I did something, anything and this is not selfishness or even some type of narrative narcissism, whereby the world revolves around me and a Mary-Sue-esque character avatar, but rather just a want for something more. This is a medium unlike any other and yet we keep choosing to pretend to be the others.

Games can be so much more but what Virginia chooses to be is not a game but a pseudo-film. It is a game in film’s clothing and while it may try to look like a film, aspire to be taken as seriously as a film can be, there is simply not enough under the cinematic skin it is wearing to be considered as such.