Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Cocoon and minor spoilers for Gorogoa.

Now and then, a game gets so popular within its niche that its magnetic field stretches beyond its genre's devotees, attracting players from across gaming's wide spectrum. Super Smash Bros. did this as a fighting game, The Last of Us did it in the narrative drama sector, and it's happened myriad times in the puzzle genre. We saw it with Baba Is You, Superliminal, and in late 2023, with Geometric's Cocoon.

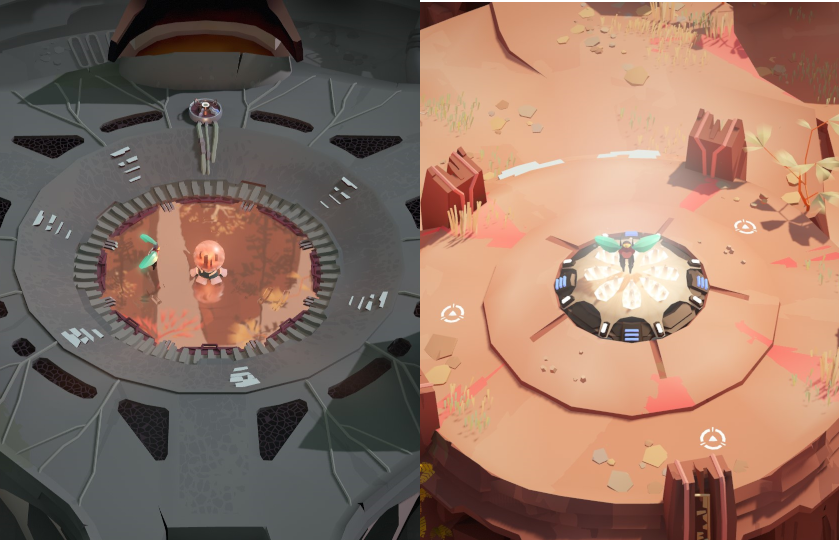

Cocoon casts us as a humanoid insect born from an egg. Our infancy is a little bland; we learn the buttons ofthe environmentalinterface and go through the motions of some simple sequence puzzles. Our explorations hit a stride once we have a couple of orbs in our thrall. Orbs power up mechanisms like moving platforms and lifts, but eventually, they also provide unique utilities. For example, the orange orb reveals hidden gantries, and the green one lets you solidify clouds of mist. Each of these balls also contains a world. If you can find a circular pool, you can put the orb on the holder in the centre of the water. If you can put the orb on the holder, you can enter the orb and complete the puzzles inside. Rubbery pads inside the orb worlds let you ascend back to the level you entered them from.

Rather than advancing linearly through a series of chambers, we make a little headway in World A, which allows us to make some progress in World B, and that unlocks some gate in World A we can continue through, and so on. The progression is multi-threaded. Cocoon has also worked out that since people in real life can transport almost any object, if we could compress worlds into objects, we could relocate entire fields or industrial hubs. As we can hold orbs when we enter other orbs, we can also place orbs inside orbs and worlds inside worlds. If we could nest objects within each other in our universe, as we can in Cocoon, then we could add their capacities to each other, which is not possible with our physics. What I mean is that 6+3 = 9. However, if I'm in my garage and I have a box that is 6m3 and I place another box inside it that is 3m3, the first box doesn't now have a volume of 9m3. The first box has the same volume it always did, minus the space that the walls of the second box take up.

To see how Cocoon subverts this geometry, let's imagine a typical brainteaser we'd encounter in it. We have three orbs at our disposal: Orange, green, and purple. The orange and green spheres each have a single pool inside, and our goal is to cram two orbs into one orb. Whether I choose to place my orbs into the orange or green sphere, I find myself entering a world with only one orb holder and, so, it would seem, the capacity for only one orb.

We have to ask, are we deadlocked? No, because we can, for example, place the green sphere inside the orange and then the purple inside the green. We were able to add the capacity of the green orb to the orange orb's by placing it inside it. It is comparable to being able to drop a 1m3 box into a 1m3 box to get a 2m3 box. If you want to see another game that models additive spaces with more emphasis on volume, look no further than Tibia: the MMO launched by CipSoft in 1997. In this RPG, each container has a number of slots, but those slots can be filled with other containers, leading to adventurers placing bags inside of bags inside of bags to maximise their carrying capacity. The only limitation is weight. In Cocoon, challenges commonly call for this technique of using one container as a vessel for others.

In puzzle games, it's typical to define a "switch" as an object that we must place a weight on to produce some specific effect. We then define weights as the items we need to place on those switches to bring about the effect. This makes the spheres the weights of Cocoon, and the pedestals its switches. But there's more purpose bound up in Cocoon's spheroids than there is in the conventional weighted cube. The orbs unseal future zones and activate mechanisms, but they also are zones, containers, and bestowers of player abilities. Through the multi-faceted practicality of the spheres, Geometric Interactive instils in us bug mindset. I've looked at insects before and thought, "Wow, how could you care so much about one lousy dewdrop?" but in this ludonarrative, I feel hyped about my dewdrop and genuinely productive handling it.

As Cocoon is a puzzle game developed after 2007, it's mandatory that we compare it to Portal. For gameplay purposes, the exit pads in Cocoon's worlds are fixed portals, and the orbs are portals we can place. Although, we can only situate the orbs in a few developer-sanctioned locations. Unlike the portals in Valve's puzzler, Geometric's never link two places within the same instanced environment; they can only grant passage between environments. And distancing itself from Portal, Cocoon is not an active physics simulation. Designer Jeppe Carlsen had previously drawn up Limbo and Inside, games that had some grounding in the principles of momentum and collision. Cocoon is almost entirely absent of these concepts.

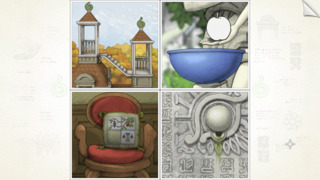

To add to that, most games that take place in a space are about moving entities around that space, whether that's pushing a cart along a track or running towards a net. Yet, the spaces themselves are immovable. In Cocoon, the geography is in flux. It's not the only game in which that's true: in The Pedestrian, ROOMS: The Toymaker's Mansion, or Gorogoa, the environment is sliced into sliding tiles that we must rearrange. Aligning them just so can make two halves of an object into a whole or give the protagonist an unobstructed climb to the next floor.

In fact, Gorogoa could be a long-lost uncle to Cocoon. We may zoom into its panels and find new scenes inside, often to step back at a later timestamp and discover the old world anew. The worlds also exist non-contiguously for much of runtime as well, and you'll leave some dimensions idle as you execute plans in others. To a point, you could peg us as playing multiple different interconnected levels at once, and that goes in either Gorogoa or Cocoon.

Where the distinction arises is that The Pedestrian, ROOMS, and Gorogoa more frequently have you thinking about the adjacency of spaces, while Cocoon takes a fiercer interest in their hierarchy. To be doubly clear, Gorogoa has more tricks up its sleeve than being a sliding tile toy, but it and the games I've grouped it with are full of these impasses where victory is a matter of deducing which two panels go next to each other. What these other games have little of, and what Cocoon has in spades, are areas where we don't just need to decide what spaces belong next to each other but how we should nest them inside each other.

Given the logic by which we mentally map places and the animations that accompany our entrance to and emergence from Cocoon's orbs, it would be natural to conceptualise the spheres and pads as existing above or below each other. Yet, if we compare them to objects positioned in regular 3D space, we can see that would be inaccurate, at least if we're using the common definitions of "above" or "below". Imagine you're standing on the second floor of a house and that there's a trampoline on the first floor, directly underneath your position. If you start walking across the second floor, away from your initial coordinates, that trampoline is no longer directly below you.

In Cocoon, we can jump off of an exit pad in one world and emerge out of the orb into the universe "above". It's like being able to jump from the trampoline downstairs to the spot on the second floor directly above it. It would be just jumping to a higher floor if we couldn't take that orb, carry it twenty kilometres north, place it in a pool, and still move "down" onto the same exit pad. Even though we are twenty meters away from the area that would have been "below" the springboard, we can still "descend" onto it. In a reversal of this relationship, any exit pad in any universe will rocket us to the location of the orb in the "above" universe, regardless of where we situated that orb.

Placing down an orb in Cocoon isn't like installing a lift in a building; our job is not to "line up" elements of the above world and the below world. Rather than picturing a straight tether linking the orbs and pads, I find it helpful to think of the universes in Cocoon like the folders in a directory tree. In Windows, you could be in C:\Program Files\, and that location could have an "Audacity" folder inside. If you were thinking of entering the Audacity directory, you wouldn't ask where in Audacity you'd come out relative to your previous position in Program Files. All you would say is that you were in C:\Program Files\, and then you were in C:\Program Files\Audacity\. In Cocoon, unlike in Portal, when you jump into a doorway, you don't think about the coordinates you'll emerge at on the other side. You don't get a choice. You simply know that previously, you existed in the hierarchy at, say, BaseWorld:\Orange\, and now you're entering BaseWorld:\Orange\Green\.

The folder simile extends to the preservation of which sub-worlds sit inside which worlds. In Gorogoa, I could have two tiles on my screen; we'll call them L and R. R exists to the right of L, and L exists to the left of R. If I slide L downwards, R does not slide down with it. The relative positioning of the two tiles is now different. But look at what happens if I do something similar in Windows Explorer. Let's say C:\Program Files\Audacity\Plug-Ins\ is a valid file path on my hard drive. If I move Audacity to the root (C:), Plug-Ins will remain a direct subfolder of Audacity. C:\Audacity\Plug-Ins\ will be a valid file path. Folders slide with each other. Likewise, if I have a hierarchy of orbs that goes BaseWorld:\Orange\Green\White\, and I move the green orb to exist directly inside of the base world, it will still have white as a direct sub-orb. I will be able to go to BaseWorld:\Green\White\. Please appreciate my Orb Notation.

To further extricate Gorogoa and Cocoon, in Gorogoa, worlds can be presented alongside each other, but in Cocoon, you are always fully immersed in whatever orb you have engaged with. So, hopping off of an exit pad in the latter game is like leaving a cinema and reconnecting with the city outside. However focused you were on the film, the exterior reality is a hundred times bigger than it. Reentering an environment you're already familiar with can still be awe-inspiring. Even the teleporters in Cocoon shook my worldview when I first stepped foot on them. In other games, disappearing from one location and spontaneously appearing at another is not too remarkable, but Cocoon gets us used to the idea that portals always take us into or out of other worlds. So, when we discover one that teleports us across the same world, we intuitively frame it as the exit pad transporting us up to the same world we're already in. How do you exit into the place you already exist in? Mind-boggling.

What's missing from my current description of Cocoon is a reason why you should care how the universes are nested. Say there's a puzzle you need to complete inside the purple sphere. What does it matter if the purple portal is inside the orange one, the green one, or no portal at all? It matters because of the powers that each orb confers. You need to hold a ball to activate its effects, but you cannot be in an orb and hold it at the same time (typically). Therefore, deciding the hierarchy of the orbs is deciding what abilities will be available to you where.

You'll recall that the orange orb makes invisible walkways visible. That means that if I'm inside BaseWorld:\Orange\Purple\, I can't use the orange orb to light up the hidden paths in the purple world. I'm unable to wield the orange orb here because I'm already inside it, and that will be an issue if I need to cross invisible bridges to get to the next area of the purple world. In fact, this limitation could be part of the puzzle. If I'm in BaseWorld:\White\Green, I can't use the white orb's power to fire bolts of energy.

The omni-solution would seem to be accessing all orbs from the base world at the top of the hierarchy, ensuring that we always have access to every power, minus that of the single orb we enter. Although, you're generally not tasked with using the green power inside the green orb or the purple power inside the purple orb as the designers understand that under regular conditions, this is impossible. If we can't enter all orbs from the base world, we'd at least want to be as high up the orb chain as possible because the fewer orbs "above" us, the fewer powers we are locked out of. That ideal scenario is frequently unattainable because:

- We often don't have an exit pad nearby to retreat to exterior realities.

- We may not have enough pools to place all the orbs in the base world and must often store some orbs in other worlds.

- Within one orb, we may need to harness the powers of another orb to conquer an obstacle and so, cannot leave it in the base world.

Under limitations 2 and 3, we are forced to decide a hierarchy for the orbs, even if it's determining whether the white ball goes inside the green ball or the green ball goes inside the white ball. As we enter each orb, our suite of powers gets smaller, and abilities that were available to us before are stripped away. Again, we have to work out what powers we need on each level. Followers of Double Fine may recognise this pattern from Stacking, their 2011 Russian nesting doll game. Cocoon doesn't go as many layers deep as Stacking, but it does feature a Russian nesting universe.

Puzzle games often prohibit our use of certain powers or items at certain times in order to stop us from relying on the same reasoning and get us thinking with exciting new rubrics. However, just greying out a move on a radial menu would be frustratingly arbitrary: an egregious example of the designer reaching into the world and flicking a switch off because they don't like it. Stacking and Cocoon provide wonderful examples of how a designer can make a limitation feel reasonable, both by tying it to real-world logic and by having the player impose the limitation on themselves. We are the ones who shed the outer dolls in Stacking, and we'd never expect to be able to use an object after we've discarded it, so there's no disappointment when we can't.

In Cocoon, we wouldn't expect to be able to pass through a doorway and hold onto it, and we make the decision of how to layer the doorways, so there are fewer hard feelings when we can't put our insectoid mits on the sphere we want. The "catch" in plenty of Cocoon's conundrums is that it appears that we need to be inside an orb whose powers we must use. We often get unstuck when we find the loopholes that reveal how we can smuggle that one orb into another or when we realise that we don't need the orb hierarchy or power we thought we did.

Cocoon joins a long line of texts that depict the universe as an onion of concentric spheres, although most previous, significant entries in this legacy have been non-fictional. In the first half of the sixth century B.C., the Greek philosopher Anaximander said that the Earth, which was then thought to be the centre of the universe, was surrounded by a sphere or spheres. That sphere or those spheres would have been the night sky.[1] Anaximedes, who is generally understood to have been Anaximder's student, added that the sky sphere was crystalline. Plato believed that the heavens moved in spherical patterns because spheres were the perfect shape. His pupil, Eudoxus, was completely orb-pilled, expounding a view of the universe that included 53 concentric spheres.[1] Contrary to popular belief, Greeks as old as Pythagoras in ~350 B.C. knew that our world is a sphere.

For the dormant civilisation of Cocoon, their crystalline spheres are one of their finest technological triumphs. One of the reasons Cocoon didn't hit for me on my first session is that there have already been a lot of dead civilisation indie games: Journey, ABZÛ, Gris, Rime, Sable, Omno, Scorn, AER, the list goes on. Cocoon didn't feel much different until the spheres made their entrance. Another way Cocoon sets itself apart from those names is that it views technology as downstream from physiology. Its fallen world was built by insects, and fittingly, tiles take the shape of honeycomb cells, the technologists take the term "drone" literally, and bridges unfold in the image of dragonfly wings. Where we typically see the height of space travel in FTL drives, the people of this society looked into a dewdrop, saw a world reflected inside and wondered whether they could make such a thing a reality. They imagine you'd exit a teleporter as if you were a larva crawling from an egg.

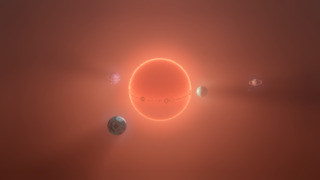

If you can collect all the orbs, master layered reality, and make it to the throne of creation, you still won't really get Cocoon. You can only achieve a divine understanding of the celestial spheres by seeing the game through to its last seconds. The world elevator ascends you to godhood. You are reborn from tiny cicada to solar-system-spanning moth, and as it turns out, the whole game took place inside another orb: a sun. The spheres we were carrying weren't just like eggs: they were eggs, and they scatter from the star, hatching into planets. A new solar system roars to life, one we watch over with our moth wisdom. While we experienced a birth at the start of the game, it is at the end that we undergo our most miraculous emergence, with the whole ludonarrative proving to have been a chrysalis for a hierarchical cosmology. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- Classical Astronomy by Robert Hollow and Helen Sim (2022), Australia National Telescope Facility.

All other sources are linked at the relevant points in the article.

Log in to comment