Steve Gaynor is the co-founder of Fullbright. He was the writer and lead designer of BioShock 2: Minerva's Den, Gone Home, and Tacoma.

It’s been a hell of a year, hasn’t it folks? For me, I mean! We’re keeping real busy at Fullbright working on a brand new game with Annapurna Interactive, and, oh yeah, my wife and I had a dang baby. She’s cute. But babies take up a lot of time, which brings us to this list. I’ve decided that, instead of an end-of-year list, I’d do an end-of-decade list… because with everything else going on, I haven’t played as much stuff this year as I’ve wanted. I’m like 4 hours into Outer Wilds, and I haven’t even downloaded Disco Elysium or Jedi: Fallen Order… so I just don’t think I could do a 2019 list justice. (Though if I did one, Control would be way up there, along with Sekiro, and the RE2 remake, and the funny Goose Game.) But, the end of a decade is a great time to look back at the games that defined the last 10 years for me. And here they are!

Confidential to personal friends whose games aren’t on this list: I still love and appreciate you, and your games! But lists are inherently reductive and arbitrary so blame the format. Or blame me, that’s also fine. Anyway, here we go!

Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Dishonored, Prey

The 2010s marked the second golden age of the immersive sim, following Thief/System Shock 2/Deus Ex all releasing within two years of each other in 1998-2000, and the return of the subgenre with BioShock in 2007. 2011’s Deus Ex: Human Revolution brought back the original cyberpunk immersive sim in grand form, bringing all the complexity and choice the series had classically offered to a modern audience; Dishonored married the weapons-and-powers gameplay of BioShock to the huge open levels and stealth focus of Thief and Deus Ex; and Prey applied all Arkane’s lessons learned from the Dishonored series to create what was basically System Shock 2++. As someone who’d been an ardent fan of the immersive sim since the genre's early days, the 2010s were a glorious time.

Thirty Flights of Loving, Packing Up the Rest of Your Stuff on the Last Day at Your Old Apartment

I was so lucky to be there for the advent of Thirty Flights. Brendon Chung actually pulled an old prototype out of retirement to complete a small game to include as a backer reward in the Idle Thumbs Kickstarter from 2012. It was this prototype that would become Thirty Flights of Loving, a new entry in his Gravity Bone series of first-person narrative games--and something that would be, to me and a number of other developers, by far one of the most influential games of the decade.

As a former host of Idle Thumbs (and a fan of Brendon’s work) I was able to play a pre-release version of Thirty Flights during the first months of work on Gone Home, and it was one of the non-combat first-person games (along with Dear Esther, Proteus, and Amnesia: The Dark Descent) that gave our team the confidence to move forward with our own first-person game with no combat--just a focus on place, atmosphere, and narrative. I’ve described Thirty Flights as “20 minutes that will change your life,” something certainly true almost eight years ago (Christ, how time flies) and I think still true today.

Years later, Turnfollow would release a similarly small game called Packing Up… which has the capacity for delivering a similarly outsized impact in a tiny amount of time. Deeply mundane and personal where Thirty Flights is fantastically cinematic, Packing Up takes place entirely inside a small studio apartment--the kind you might have lived in for your last year of college--on the day you’re moving out. You spend your time going back through all your stuff, reminding you of the moment in your life that this place represents via the things that accumulated there, and who this person was that you’re now looking back on. The ending is breathtaking, not for its scope or scale, but for its simple expansion of the game’s bounds, in just those last moments. I love both these games for what they are, and what they tell us games can be. And you can experience both of them together in less than an hour. Don’t you sometimes feel grateful just to be alive?

The Last Guardian

The third piece in Fumito Ueda’s trilogy had a long, dramatic development period, going from a PS3 exclusive system-seller to a title that launched well into the maturity of the PS4’s life cycle. It somehow felt like it missed its window; I at least got the impression the game was quietly received by the time it finally arrived (having, at a number of points, seemed like it might never be released at all.) But to me, The Last Guardian is a masterpiece, and once I played it the sheer number of years it spent in development all made sense.

Both as a player and game developer, the sense of scale and life in the game is just astounding. The experience centers around Trico, this independent, living, giant creature that inhabits the game, and your relationship with him as a young exiled boy just trying to get home. The dynamism and presence of Trico, a creature that seems to really think and react to you and the world as an independent entity would, is entrancing. And as a game developer, the technical undertaking of this complex AI navigating this fully physics-driven world--where, in some cases, Trico will be balancing on a physics platform that’s dangling from a rope, while you the player are hanging onto Trico’s fur and balancing on his back as he jumps from physics platform to physics platform above an abyss--all of that stuff is just so incredibly hard to make work in a video game on a technical level… and The Last Guardian absolutely works, both technically and as an engrossing, emotional experience. It is one-of-a-kind; it is about the unspoken power of loyalty, determination, and caring. Everyone should play The Last Guardian.

Hitman/Hitman 2

I’ve been a dedicated fan of the Hitman series since its very first incarnation, and I’m one of those people who insisted Hitman: Blood Money was a top-5-of-all-time game (once you got past the tutorial level), a high point of the series that no successive Hitman game was able to match, much less surpass. Well, clearly some folks at IO Interactive agreed, because 2016’s Hitman (and 2018’s Hitman 2, a direct sequel that’s as close to a full-length expansion pack as anything) was a return to everything that made Blood Money great, complete with a ton of interface and usability improvements.

Hitman and Hitman 2 are, quite knowingly, dark comedies. Dark because you do play a genetically-engineered agent of murder chaos tasked with assassinating his target in each mission, but comedy not in what the game tasks you with, but in what the game allows you to do. The core mechanics of Hitman have always lent themselves to the comedic, specifically Agent 47 being able to dress up in a variety of costumes to disguise himself in each level, as well as the variety of creative ways to take out your target beyond a simple garrote or silenced bullet. In a Hitman game you can sneak into a heavily guarded compound in your trademark suit and snipe your target from a hidden vantage point, no one the wiser, or you can dress up in a flamingo mascot costume and surreptitiously push your target over a railing into the path of an oncoming race car. Hitman 2 is a game where you can impersonate a real estate agent to take your target on a full tour of a house for sale before causing them to “accidentally” trigger a hidden security system and blow themselves up. There are multiple missions where you can trick your targets into assassinating each other, then jump on a jet ski or motorbike or helicopter and ride off into the sunset. Hitman and Hitman 2 are wonderfully absurdist sandboxes of death, the pair a triumphant return to the series’s highest point--a pair of games I couldn’t be more grateful for the existence of.

Butterfly Soup/Dream Daddy: A Dad Dating Simulator

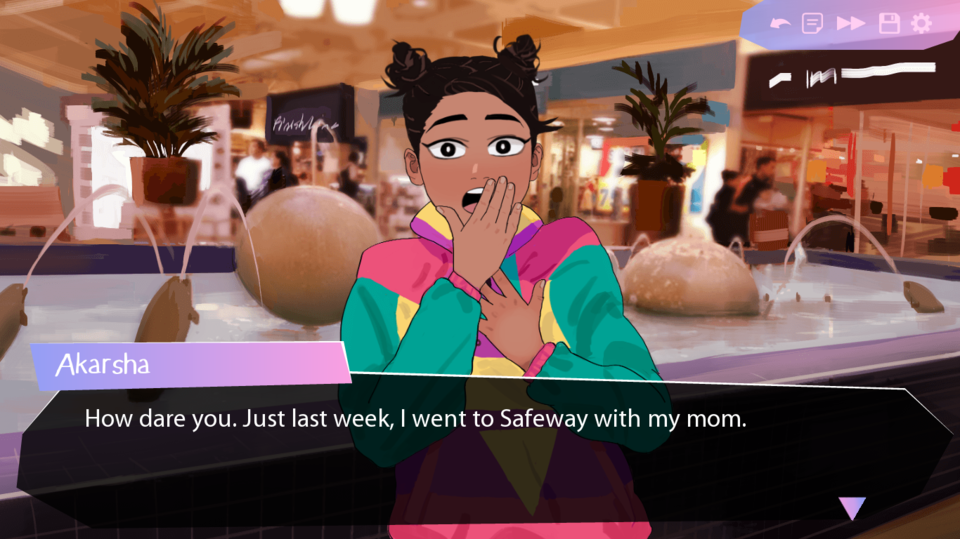

I’d never been much into visual novels, but a pair of indie games that came out in 2017 changed my whole perspective on the genre. Butterfly Soup and Dream Daddy both take the visual novel formula and apply it to something uniquely personal, as well as, incidentally, incredibly gay.

Butterfly Soup is one of those games I love for being just exactly what its creator wanted it to be. There was no game out there about a group of young queer Asian women who bonded over a shared love of baseball, and so Brianna Lei had to create it. The lived experience of the subject matter comes through in the game with a clarity and directness you can’t help but be drawn in by, and the writing is some of the funniest, laugh-out-loud stuff I’ve ever encountered in a video game. The authenticity and humor of the game dovetail into an ending that’s disarmingly touching and understated, leaving the player on a pitch-perfect note of nostalgia and longing that lasts far beyond the closing credits.

Dream Daddy is likewise just funny as hell, starting from a premise that reads as a much sillier escapist fantasy than Butterfly Soup’s: you’re a single dad who moves into a neighborhood populated entirely by other, very hot dads, any of whom you can date. On the surface these dateable dads appear to be cartoonish archetypes (gym rat dad, big bear dad, repressed religious dad… goth dad?), but Dream Daddy ends up being all about real empathy: empathy for the other dads you date and their personal anxieties, phobias, and foibles as you get to know them as people, not categories; empathy for the very real teenage tribulations of your daughter who’s about to leave home for college; and empathy for yourself, a simple dad just trying to do his best. Both these games balance raucous humor with an earnest humanity that make them incredibly vital, fundamentally valuable experiences.

Resident Evil 7

There is something about Resident Evil that works so well in smallness. The original game was all about an encounter with just one shambling zombie being terrifying; Mr. X and the Nemesis in RE2 and 3 respectively amped this up by acting as singular, nearly unstoppable presences that stalked you throughout the game. I love RE4 (locked in perpetual battle with Super Metroid as my favorite game ever) and its feeling of fending off hordes of infected villagers as they bear down on you, but the best, scariest moments in that game are when it’s just you against one terrifying adversary, such as the xenomorph-like horror you face in the tunnels beneath the castle, or the Regenerators that stalk you in the labs late in the game.

Resident Evil 7 rekindled that feeling in full force by going back, in many ways, to Resident Evil’s roots. Once again you’re all alone in a decaying mansion, filled with secret passages and strange contraptions. But RE7 is the core series’ first foray into first-person, putting you directly inside these claustrophobic environments, face-to-face with what you’ll find. And in its best sequences, it’s just you against one, terrifying enemy, causing you to constantly look over your shoulder as you search for a way out of this nightmare scenario, stalked at every turn. RE7 brings real survival horror back to the series with an immediacy and confidence that’s just thrilling to see. In 2019 we had a wonderful remake of RE2 that sticks more to the original games’ form (and an RE3 remake in the same style is on its way), but I hope we’ll continue to see more Resident Evil games in the vein of RE7, continuing to explore what else might be found further down that game's path.

Dark Souls/Bloodborne/Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

What more is there to say about the Souls series that hasn’t already been talked to death by players, journalists, and game developers? The influence of Dark Souls on game design of the 2010s is so significant and pervasive as to have become a cliche, but that intensity of influence is certainly well-earned. Dark Souls is one of those games that seems so unlikely; that is so difficult, obscure, and idiosyncratic that it’s hard to imagine how it actually got made, and to such a high and exacting standard, despite having so few precedents. And that is in all likelihood why it was such a breakthrough: something that was so singular, unexpected, challenging and rewarding that as a player you just had to be a part of it. Dark Souls is a game that is the result of such a vision--of what the game would be, how players would interact with it, how online interactions could support a game’s mysteriousness and strangeness, the confidence that in spite of giving the player precious little assistance--that people would dig in, engage with this weird, impossible thing, and explore every little bit of richness the game had to offer. As a game designer, it really is inspiring. Which, I know, is a cliche, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds

I have like 500 hours in PUBG and I’m still terrible at it and I still love it. Maybe that’s the sign of a great game? Or maybe the sign of a great game is spawning an entire subgenre, including one of the most commercially successful games of all time. I just know I stepped away from PUBG for like a year and a half, tried a bunch of the games it inspired… and now I’m back at it on the original, and enjoying the hell out of it. It's singular, unforgiving, and still kind of janky, but through it all it retains some kind of weird busted magic that can’t be duplicated.

Yakuza 0

My arc with the Yakuza games is kind of a parallel with the Hitman series. I was a huge devotee when the first couple of games came out, fell off the wagon during the series’ middle era, and then dove right back in with Yakuza 0 on the PS4. And god damn I love it. I love the '80s Japan setting, recreating the highs of the economic bubble while foreshadowing the lows that will follow; I love it as an origin story for young Kiryu, the yakuza with the heart of gold we’ve gotten to know over half a dozen other games in the series. And, like all the Yakuza games, I love its strange tonal mix of high drama and completely goofy, self-aware side quests, its overly-involved minigames and tangents, and all the little details you notice while exploring Kamurocho for the umpteenth time. I’ve really enjoyed other titles in the series, including the recent spin-off, Judgment, about being an ass-kicking private eye in the Yakuza universe, but there’s something specifically about the verve and vitality of Yakuza 0 that makes it the high point of the series--and one of the high points of the 2010s--for me.

The Last of Us

The 2010s were the age of “prestige television," and The Last of Us was, in many ways, the bellwether of AAA “prestige games.” High production values, self-serious, but earning its sense of gravitas, The Last of Us stripped down the swashbuckling and setpieces of the Uncharted series and set its focus on two people struggling to survive a broken world. The Last of Us is that rare instance of a production’s budget going toward all the small, quiet things that give it life, along with the big, bombastic things that make it a blockbuster. It’s the kind of game that makes the scale of a AAA production feel justified, not just for spectacle, but for soul--a game that helped defined the medium’s last 10 years.

So, what now? I guess by the time I write a list of “my favorite games of the 2020s” my daughter will be in 5th grade, and I’ll be a desiccated pile of dust, officially the oldest man the world has ever seen. Til then!