Austin Walker is an Editor at Giant Bomb. He likes giant robots, continental philosophy, and tabletop role-playing games. His weekly column, Off the Clock, runs every Monday(-ish.) Follow him on Twitter.

Though I only joined the Giant Bomb in June, I made my actual debut to the site this time last year with what I’ve heard was a very strange Game of the Year list. It felt surreal to me to be on Giant Bomb--after all, the site’s Game of the Year content had become something of a holiday tradition for me (as I imagine it has for many of you too). This year, there’s a video on the site of me building a mecha model to the tune of royalty free J-Pop. So. Yeah. Surreal.

Looking back on last year’s lists, I’m starting to think that 2014 gets a bad rap. Yes, there did feel like there was a bit of a vacuum in the AAA space. But in retrospect, I think last year was prefiguring this year in a pretty big way. This year had no lack of quality AAA games, but it was also a year where smaller games found very large audiences. With access to better tools and the continuing rise of digital distribution, games have become increasingly diverse. That means that while there's still some crossover in personal lists this year, there's also an incredible amount of variety at play. What a rad thing, right?

It’s also made creating this list feel impossible. How do I make a list of only ten without leaving out something--large or small--that I wholeheartedly enjoyed? How do unique ideas compare to incredible execution? In 2015, with the ascendancy of watching-other-people-play-games, can I include a game on this list that I’ve literally never touched myself?

At the end of the day, I think the only way to do it (as with all criticism) is to be radically honest about the things I've played this year. So. Here we go.

10. Her Story

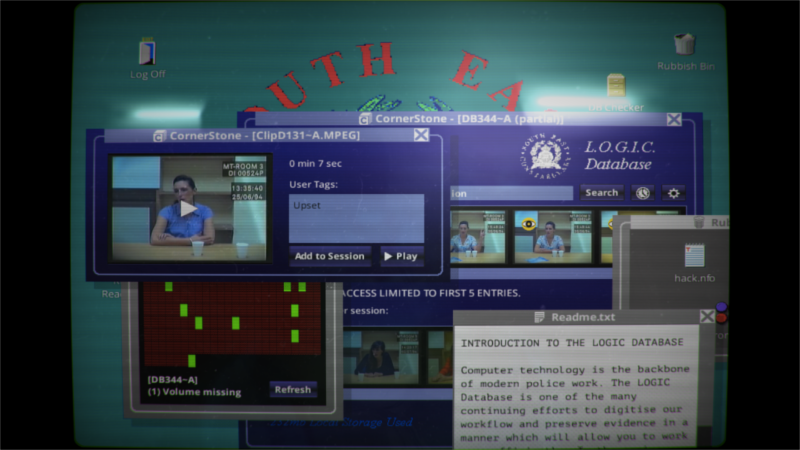

Though I’ve cooled a bit on the database-diving detective game Her Story since originally playing it, I can’t overstate the intrigue I felt when I first booted it up or the intensity of that first session. A Sunday afternoon disappeared as I was drawn in by the hums and clicks of an old PC, the garish interface of the police video directory, and Viva Seifert’s (mostly) striking performances.

Not only is Her Story a solid, non-linear true crime story, it’s also a catalyst for some fruitful conversation in mainstream games criticism. Does a game owe us any sort of designated resolution? What narrative and ludic value is there in dead ends and red herrings? What is it that people can do for us in games that polygons still can’t--or at least not for an affordable price?

There are other games that tell better mysteries and that dive deeper into detective genre, but no video game has ever made me feel as much like I was investigating a crime. I’m incredibly curious to see what other designers learn from Her Story, and I suspect we’ll be looking at more and more faux-PC interfaces in the years to come.

Speaking of which...

9. Cibele

Here’s what you’ve probably heard about Nina Freeman’s Cibele, from both its most ardent fans and its most skeptical critics: By referencing things like LiveJournal and MMOs, It speaks to a generation that hasn’t yet had its particular version of adolescent romance spoken to in an interactive form. If you can see yourself in Cibele, it will mean a lot to you.

That version of the story isn’t untrue--and it was even worth saying back when Cibele first launched--but it undersells the game seriously. I’ve been pretty frustrated by the way the discourse around Cibele has been anchored to this question of identification with the game’s story. Because it isn’t only that Cibele does something particularly novel, it’s that it does it well.

Freelance critic Nick Capozzoli places Cibele inside of a genre he calls the “fantasy pen-pal format,” a style of game that is currently emerging into the mainstream via games Lifeline and Emily is Away. But Cibele is a more intricate narrative vehicle than its peers. Emily is Away struggles over how much agency to give the player to its real detriment, muddying whatever moral lesson might have been intended. Lifeline tells an enthralling sci-fi story, but the seams in the storytelling (especially its use of railroading) become clear after only a little pressure.

Cibele, on the other hand, smartly distinguishes where and when player has input. You comb through archival material (like blog posts and photos) to piece together the protagonist’s past, including the time spent between chapter breaks. You respond to IMs and skim through social media, but never choose your own responses. You listen in on a dialogue between the two leads, the sort of words that are stilted by youthful awkwardness and that move the speakers like trains towards each other.

The line is clear: The player can look backwards however much they want and in whatever order, but what comes next is out of their hands. You’re playing as Nina, but you’re also an onlooker, helpless to stop the impending crash. Cibele is worth talking about not only because we’ve all crashed like this, but because it’s rare to see such a disaster handled with such elegance of design.

That’s not to say that I’m opposed to games that play on personal identification and nostalgia though because listen, if you wanna talk nostalgia, we can talk nostalgia...

8. Dragon Ball XenoVerse

I first played Dragon Ball XenoVerse 15 years ago in a dream. That’s not a metaphor. 15 year old Austin literally dreamt of playing a time-warping “what if” Dragon Ball Z game that featured character creation and light RPG mechanics. But even in that dream I didn’t think they’d actually pull the damn thing off.

After all, the Dragon Ball Z games I played as a teen--whether imported or emulated--were janky as hell. Even the stand outs (like Dragon Ball Z: Legends) were only ever good for Dragon Ball games, rarely ever simply good.

Somehow, XenoVerse is great. The punches feel powerful, the twists to the well known DBZ canon are clever, and the progression system hooked me hard (though I will say that it doesn’t do a good enough job of communicating that grinding for drops just isn’t worth it early on.) Even the multiplayer is solid, and contrary to rumors, the servers are still live!

Earlier this year, I spent a bunch of words trying to figure out what drew me to the world of Goku and Piccolo and Vegeta, why it was that even at thirty years old Dragon Ball Z feels important to me. I’m still not sure I have an answer to that, but I know that something in me lit up when I finally got to make make a Super Saiyan named Wiz KaleLeafa.

And no, I will not apologize for that name.

7. Elite: Dangerous

When I think about some of my favorite games, I realize that many of them are built like clocks. Carefully structured, complex machines of art that produce a grander response than any one of its component parts could inspire on its own. An individual piece might be flawed, but when taken together, the group of parts comprises such a unity of effect that it’s hard not to be overwhelmed. “Greater than the sum of its parts,” as the saying goes. That is not what Elite: Dangerous is, which is why it’s surprising that I love it so much.

Elite: Dangerous is that other kind of great game, the kind where the wide view reveals numerous flaws and deficiencies, but when you take any single element on its own, those problems fade away.

It is a game of dozens of little perfect moments: The hefty ka-thump as you land your ship in the busy commercial space station. The nerve-wracking sirens that fire as a pirate tries to yank you from warp speed, and the panicked feat of lining up an escape vector so that you can get away with your life (and cargo). The strange combination of awe and mundanity as you spend five long minutes refilling your ship’s fuel stores by skimming across the aura of a glowing star. The surprise of arriving to a new system and seeing your first capital ship, a massive thing orbiting some station, cutting an imperious figure, silhouetted against the planet below. The pyrrhic victory of limping in space-dark silence back to port with a busted cockpit window and only a few last gasps of oxygen in your tank. Hey, you should see the other guy.

Elite: Dangerous doesn’t have any grand quest lines or deep RPG-like progression mechanics. There’s serious repetition and a long grind between major ship upgrades. These moments that I love so much never cohere into something that looks like other big budget games. But they never have to. All on their own, they made Elite: Dangerous a singular sort of experience for me this year. I can’t wait to see what comes next.

6. Grow Home

So, here’s the thing. I don’t like platformers. I grew up loving them, and I still respect the genre a whole bunch, and I like to think that I can see what sets the best platformers apart from the rest, but I just don’t enjoy them. Whenever I’m playing a platformer it feels in my bones like I’m waiting for a bus. No matter how exciting or innovative or colorful the characters bouncing around screen are, I’m only ever just passing time until something, anything, else catches my attention.

Here’s the other thing: I really, really like Grow Home.

Maybe it’s that the bumbling robot made mastering the controls so much more rewarding for me. Maybe it’s the fact that hours into playing I could look up (or better, look down) and see the web of vines cutting through the sky in exactly the way I arranged them. Maybe it’s the year: In a time so chaotic for me, there was something peaceful in disappearing into something bright and warm and small. Honestly, the brevity alone might mean something: Maybe I only have four to six hours of platformer in me every year, and being able to have a complete platformer experience in a single sitting is pretty amazing.

More amazing? I’ve spent the last few years railing against Ubisoft’s reliance on climbing towers and finding collectibles. It’s felt like design-by-numbers. Grow Home takes both of those things and shows that there’s nothing innately wrong with them--that if executed well, those objectives still have lots of power in them.

5. Wheels of Aurelia

If “pen-pal fantasy” is one emerging subgenre of game, here’s another: The road trip game. Last year’s Glitchhikers impressed many critics with a surreal, nighttime blend of driving and dialog. Earlier this year, Three Fourths Home surprised me with its stark visuals and starker take on the unavoidable complications of life. The Crew was certainly not meant as a road trip game, but goddamn is that when it’s at its most absurd and best.

Wheels of Aurelia joins this mix, blending an OutRun style branching highway with stories of personal rebellion and a whole lot of style. Playing as Lella, a woman with a leather jacket and a mysterious past, you speed down the highways of 1978 Italy while chatting with whoever you’ve got in the passenger seat(s). That includes ingenue runaways, hitchhikers who want to talk to you about UFOs, rock and roll jams, and a few other surprises.

There’s a low hum of melancholy throughout Wheels. Maybe it’s because the characters know that they’re exactly a decade too late for their sort of radicalism to change Europe, maybe it’s because they’ve suddenly been made to face some very adult problems, or maybe it’s because the highway is never as long as they need it to be.

It took me way too long to get to Wheels of Aurelia, but I’m so glad that I did.

4. Fallout 4

I’m incredibly thankful I didn’t have to review Fallout 4, because if I did, I’d have to spend a lot of time considering what some hypothetical “average” player might desire or expect from the game. I’d have to knock it for its start-stop narrative pacing, for the “jankiness” that so many people can’t stand, for being iterative instead of revolutionary. But boy, would my heart not be in any of that criticism.

The fact is that when I come into a Bethesda game, I don’t care who or what the game sets up for my character. I’m not playing as Bethesda’s man-out-of-time shmuck, I’m playing as Smith July, scavenger and smooth talker. I poke curiously at the main story (hell, I maybe even complete it), but mostly I focus on exploring the world and meeting its inhabitants, and wondering what someone like Smith July would do to get by in these places. I waver between passively letting Fallout 4 wash over me and actively going out of my way find the edge cases that break the game’s design.

I can see how the things that set Fallout 4 apart from its predecessors--the crafting system, the settlements, the changes with Power Armor--might not mean much to a lot of players. But they’ve been huge for me, setting up new gameplay loops that devour hours. What used to be a trip to the nearest NPC to offload a bunch of weight in exchange for caps has now turned into a visit home where I look around and figure out what improvements can be made. It’s not the first time building and decorating has been fun in a game, but it’s the first time that it’s felt so integrated into a game like Fallout 4.

The refrain about Fallout 4 is that it’s “more Fallout.” Thank Atom for that.

3. Galak-Z: The Dimensional

Listen. No, really, listen.

That song is Galak-Z. The pumping synthbass is your engines, guiding you through the needling plasma blasts of the enemy, guiding you towards your solo: A quick transformation into your mech mode, your grip tightening on the hilt of your laser blade, you bounce from one enemy to another, bounce bounce bounce, and then the rhythmic, explosive booms.

Where Elite: Dangerous never fully coheres despite its individual pieces being incredibly strong, Galak-Z’s is monistic. Each of its individual pieces--the sound design, the procedural “episodes,” the arching motion of the ships--all reflect a broader totality. A really fucking cool totality.

Best of all, the PC release is smoother than ever, and shipped with an “arcade” mode that offers players a non-roguelike option. If you haven’t checked it out yet, you should.

Now give me Season 5.

2. Undertale

God, where do I even start with Undertale. I mean, I’ve already written about how highly I think of it, and I’m worried that any conversation at this point needs to expand in scope to be useful or insightful. I’d have to talk about Toby Fox, who is at once entirely approachable and somehow elusive. Or about how the heat around Undertale’s performance in GameFAQs' “Best Game Ever” ties into ongoing ideological debates in the larger culture. Or about the ongoing development of niche fandoms (in general) into meaningful market forces. Or to return to what I said at the start of this thing: Games in 2015 are more fractured than they’ve ever been, and maybe (maybe?) that’s a good thing.

But god, I just... man. This isn’t the place for that. This is the place for me to say again that Undertale is a really good game and that I hope you’ll find the time to play it. Just put aside everything you’ve heard about it, try not to bring in any of the expectations that so many people have put onto it, and just give it a shot. It is a weird, charming, beautiful thing that deserves that much.

1. Invisible, Inc.

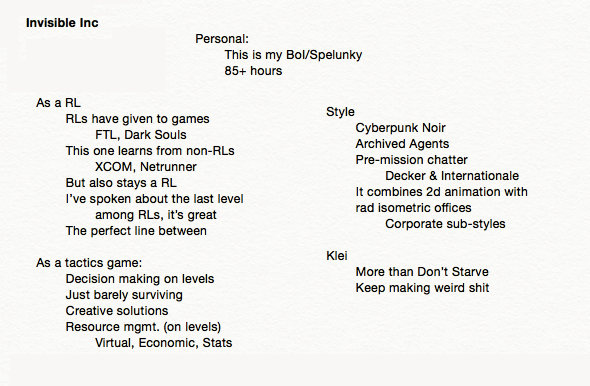

There’s a point during this year’s Game of the Year podcast deliberations where Alex warns everyone else at the table about my fervor for Invisible, Inc.: “Austin’s prepared,” he says. “He brought notes.”

I did bring notes. Here they are:

I hammered these out during a moment of clarity (or was it a fugue state) midway through the week of debates. “Oh,” I realized to myself, “Invisible, Inc. is my favorite game here and no one else is going to mention it, except maybe in passing. I have to go to the mat for this thing.” Why did I feel the need to do that? Because Invisible, Inc. is one of the best designed games I’ve ever played.

I make that claim confidently, but I also know that because of the diversity of games in the world now, it’s a hard one to support. Saying that a game is “well designed” means myriad different things, especially these days. Cibele is “well designed” in both its narrative structure and in the way it divides different styles of interactivity. Grow Home is “well designed” in that its creators recognized that the most fundamental verbs the player uses while playing are so enjoyable that they shouldn’t distract from them with clutter or bloat. Super Mario Maker is “well designed” because it leverages a mountain of player knowledge to ease its users into understanding level creation.

It's possible to understand each of these as wildly different sorts of design. But in each case, these elements reflect a careful construction process that considers the desired experience of play, the expectations of players, the contexts of release, the method of input, and a holistic vision of the game being made. So, when I say Invisible, Inc. is “one of the best designed games I’ve ever played,” that is what I mean that the team at Klei that built it achieved.

Invisible, Inc. functions on three levels, and each level is fascinating in its own right. At the ground level, you control a group of cyberpunk super spies, outfitted with augmented abilities, some future-tech gadgetry, and a weapon or two. Here, the game is a stealth-based roguelike that requires the player to make analytical decisions based on limited data (and in the process, attempt to gain more data.) Even simple problems lead to complex (and fun) instances of resource management.

You come to a locked door, but good news, you have a keycard. Do you unlock the door? If so, you’ve built a path of egress for yourself, but enemy guards can now also use that door. But hey, you gotta go that way, so you unlock it. Now what? Do you peek into the next room before heading in? If so, do you check with the door closed or do you stand safely to its side, open it, and then dip your head around for a quick look? If the former, you’re safer, but you get a less perfect picture of the room. Or maybe you decide to just charge in--time is a resource too, after all. Are you prepared to spend resources to deal with whatever problems are on the other side? If so, which resources? Do you blow your cloaking device and hope that you don’t need it again before it’s recharged? Are you willing to spend one of your very limited armor piercing bullets? Or do you slip up to the second layer of play and use one of your virtual resources to solve the problem.

In the second layer you manage "Incognita," an AI that can subvert enemy security and give you access to more information about the level and game state of the ground level. But many of these things are locked up, protected by firewalls which themselves are patrolled by corporate "daemons," and suddenly you're back to planning.

You notice that there’s a turret behind the locked door. The sort of thing that will kill your most important crew member in a single blast. Do you try to sneak your agents past it, or spend the virtual resources to hack its power source and shut it down? Or maybe you want to hack the turret directly,since once it’s on your side it can provide cover fire during your escape. Good call, except it has a nasty piece of defense software on it. Could be something small, like the Blowfish Daemon that simply advances the alarm severity by a couple of steps... Or it could be something nasty, maybe a Countermeasure that calls a new guard to investigate the area, or worse, a Paradox, the sort of thing that totally locks down your ability to hack for multiple turns. Good thing that you’ve played the third layer so well up 'til now, because you have just the solution to this problem.

If layers one and two are about tactical decision making, then layer three is where strategic thinking comes into play. In between corporate infiltrations, you spend the credits you’ve captured on stat and gear upgrades for your agents, and then decide where to head next.

You could’ve gone to a Detention Center, where you might’ve located another agent to recruit to your squad. Or maybe to the Security Dispatch, where the latest tech is held. Or you could’ve decided to use that special code you found in a previous mission so that you could breach into the deepest reaches of a Corporate Vault. But instead, you went after a Kelfried and Odin Server Farm and while you were there you picked up a little program called “Hunter.”

You point Hunter at the Daemon protecting the turret's firewall and in a blink, it’s toast. You hack the gun emplacement, bust through the door, end your turn, and... a guard walks around the corner. God damn it. Now what? Do you…

It goes and goes and goes like this. Each challenge in front of you reflects so many previous decisions, and so each choice you make has weight. It also means that when you get it right, you feel clever as hell. Can’t find the power supply to get through the laser grid? Knock out a guard and drag him through it: His security clearance will deactivate it and let you pass through. Have one agent trapped in a corner? Have another sprint loudly down a nearby hallway to grab enemy attention. These little moments bubble up because the game has been seeded with them by its design. They aren’t scripted, but emerge from set of well configured rules and are then brought to life by a visual style that draws as much on Alphaville as it does the animation work of Genndy Tartakovsky.

Invisible, Inc. is a game of learning how to do a lot with a little, of information control and resource management, of sharp visual design and fantastic theming. More than anything, though, Invisible, Inc. is a game that is beautiful to play. That’s it, really.

Last year, Invisible, Inc.’s early access release was my eighth favorite game of the year. This year, between its launch release and its fantastic expansion pack, it has become my favorite game of the year. By far. I stopped writing this list at least twice so that I could play through a quick mission (or two… or three), and the second I’m done I’m going to dive back in. Wish me luck.

Honorable Mentions: Rocket League, Subterfuge, Life is Strange, Super Mario Maker, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain