Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Half-Life, Black Mesa, and Portal 2, and moderate spoilers for Portal and Half-Life 2: Episode Two.

Last week, I talked about Half-Life as the last great lurch forward in 90s shooters. I reviewed a game with a weapon set that, while sagging around the edges, contained some of the most reliable core firepower you can get your hands on. I also described how Valve designed enemies with a mind for setting up interesting player choices. But most games aren't only rules, hazards, and tools. They are places; places with an atmosphere, a purpose, and a history that, as the protagonist, we continue the writing of. We can't talk about Half-Life or Black Mesa without talking about Black Mesa.

These FPSs braid an almost unbroken tether between you and their research facility by only including one cutscene, and even that's from the first person. They eschew out-of-body experiences that might remove you from your perspective as a researcher in this fragmenting complex.[1] We're going to talk more about that complex today. Last time, I only assessed the weapons and enemies that I had something to say about, and in this article, I'm taking the same approach to stages. I'm also going to skip over Black Mesa Inbound, as we already have the introductory tram ride in the bag. If we're keeping to the schedule, we should pick up at Anomalous Materials.

Anomalous Materials, Unforeseen Consequences

Anomalous Materials is the mission where it all goes wrong. Black Mesa's analysis of an unidentified mass turns the facility into an interdimensional welcome mat, and all manner of extraterrestrial predators wipe their feet with it. I could sit here and write out an explanation of the "resonance cascade" as a character motivator or a scientific phenomenon, but if you really want to understand it, you have to accept it as a metaphor for the real-life Chernobyl incident. In 80s Ukraine, you had an experiment at a scientific facility centered on a bizarre material (uranium-235). Nuclear plants like Chernobyl's work by using a fission reaction to heat water, turning it to steam. That steam rises, pushing a turbine, and the kinetic energy of the spinning turbine is converted to electrical energy. But when you cut the reaction, the turbines don't stop spinning immediately; they take a very long time to wind down.[2]

The engineers at Chernobyl wanted to know if, in an emergency, they could use the spin-down to keep the reactor's water pumps running in the case of a power outage. But those technicians ignored safety procedures and warning signs, pushing their reactor beyond operational limits in order to please seniors in the Soviet hierarchy.[2][3] When they tried to abort the experiment, they were overruled by their supervisor, and by the time they worked out that they were cooking a meltdown, it was too late to stop the chain reaction.[2] Their experiment killed thousands. However, many of the heroes of the hour were also scientists who worked tirelessly to contain the danger, some of them putting themselves at extreme risk.[2][3]

Half-Life was released twelve years after Chernobyl, and in its second level, Anomalous Materials, you head to a test chamber as scientists complain that equipment has been breaking all day. A control panel explodes in a shower of sparks, with one of your colleagues shouting, "It's about to go critical". Another responds that the machinery wasn't built for the upcoming experiment. Then, they start cutting corners, rationalising it at each turn point. They overcharge the spectrometer to 105%, but they need to show promising results to the administrator. They deviate from standard procedures, but it's fine because Gordon is a highly trained professional. There's a discrepancy in the readings, but it's not a problem. Probably. When it does become a problem, Doctor Kleiner tries to shut down the machine to find they are past the point of no return.

After the cascade, in the level Unforeseen Consequences, we find the same scientists who were minutes earlier poring over equations and preparing equipment lying still and soulless. Here and there, the aliens that have claimed their lives still creep around the labs, and more shock troops teleport in. After the fact, the dead can't be brought back, but one scientist can minimise the aftershocks: Gordon Freeman.

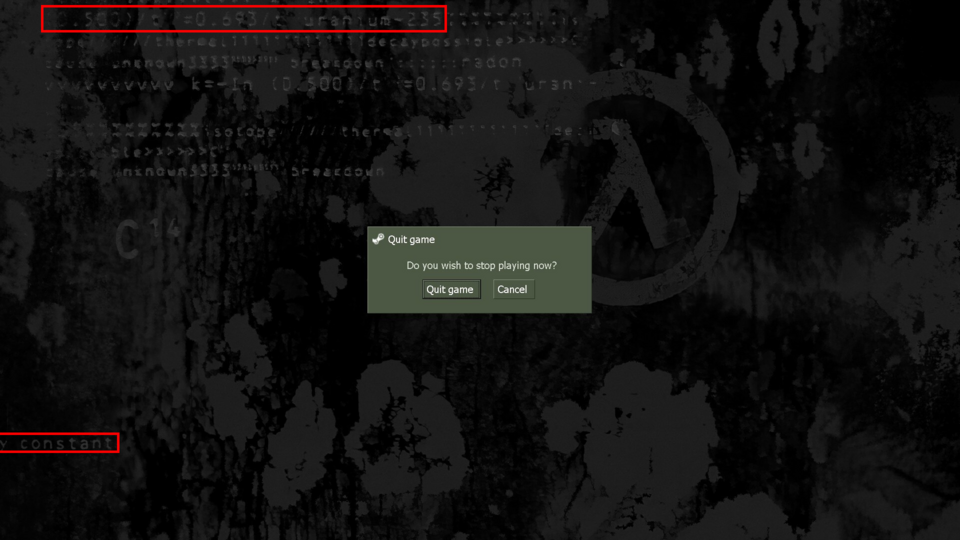

There are also references to atomic physics all over this drama. Gordon's HEV suit has a built-in Geiger counter, one frequently triggered by radioactive leakage in the facility, and the level Lambda Core sees us activating a nuclear reactor. The term "half-life" represents the amount of time it takes for half the radioactive atoms in a substance to lose their radioactivity. The series' logo is the lambda, which is also the seal on Black Mesa's internal nuclear plant and, in the game Black Mesa, the marker of supply caches. This Greek letter denotes radioactive decay constants. The decay constant is the ratio of the radioactive atoms in your sample to the rate at which their radioactivity blinks out. On Half-Life's box and the game's main menu is an equation for calculating a half-life: you divide ~0.693 by the substance's decay constant.[4] The menu also contains the terms "decay constant" and "uranium-235".

In Black Mesa's Unforeseen Consequences, a researcher references Henri Becquerel, the man who discovered radioactivity. Even the name "resonance cascade" invokes a runaway chain reaction. There is little reason for the game to make these references to atom smashing outside of referencing Chernobyl. The nuclear reactor in Black Mesa is a minor character in the story, and the resonance cascade is not nuclear in nature.

Office Complex

It's in this fourth level that we begin to see how the rip in reality has maimed the functionality of Black Mesa. Doors are blocked, offices are abandoned, and windows are smashed. The facility appears as a believable scientific institution because, in addition to the rooms where the magic happens, we see the vast network of supporting services that the experimentation relies on. About half of the game's levels have us visiting one of those subnets.

There are the offices that file paperwork in Office Complex, the generators that electrify other departments in Power Up, and the transport layer that ferries scientists between jobs in Black Mesa Inbound and On A Rail. We tour the warehouses that store the materials for all this production in "We've Got Hostiles", and we see how Black Mesa disposes of waste from its operations in Residue Processing. Finally, in Surface Tension, we tip-toe around the guard booths that keep researchers safe. It makes the opening chapter, with its diorama of an interconnected research site, a microcosm of the whole game. But in so many levels, the developers ram home what the resonance cascade has meant for Black Mesa by showing you these hubs unable to execute their respective services. The generators are parched, the subways rerouted, and the guards flushed out of their security booths. In Office Complex, no admin is getting done amongst the exposed wiring and the Zombies ripping skin from muscle.

On the bright side, Office Complex comes after you've had some time to catch your breath post-meltdown and is your first opportunity to regroup with building security. You might be able to argue that this is Half-Life's horror level. It has one too many Headcrab-infested air vents for comfort, but you need to squeeze through them if you want to make it to the surface and escape the facility. This is also a level where Black Mesa (the game)'s modern lighting shines, so to speak. There are too many blinding bright corridors in the original Office Complex for it to feel like every shadow could hide a zombie or that a total shutdown of the plant has occurred. Black Mesa bathes the white-collar workspace in a thick darkness, only occasionally punctuated by errant beams of light that let features and actors stand out against the background. This shading will later set the tone for the conspiratorial laboratory level, Questionable Ethics.

You can also thank Black Mesa for rectifying Half-Life's overbearing acoustics. In 1998, the GoldSrc engine pushed the envelope by letting floors vibrate with your footsteps and the clank of your Crowbar bounce off of walls. In 2024, it's just irritating. You can also hear enemies through walls with no muffling, which muddies data on when an alien is near you and when it's not. Black Mesa's sound is less distracting and keeps you in the moment.

"We've Got Hostiles"

The fifth chapter, "We've Got Hostiles", greets you with a welcoming committee of Turrets. I prefer Black Mesa and HL2's handling of Turrets to Half-Life's. In the base game, a Turret is an enemy with health like any other, and depleting that health blows it up. In the revisits to Half-Life's world, you play schoolyard bully, defeating Turrets by knocking them down. It makes you think differently about what you're using your weaponry for and better matches the flimsy profile of the devices to their mechanics. The Source Half-Lives also let you carry the machines as impromptu weapons, which feels like a mischievous exploit of the enemy's tech.

But the robots aren't the sharpest left turn in "We've Got Hostiles". At the start of the level, you hear an announcement that the military has taken over the research centre. A nasty realisation occurs when a scientist yells, "we're saved", runs towards a marine, and is summarily executed. The military isn't here to save you; it's here to cover up the incident. Who do you think set the Turrets?

Half-Life was partly inspired by Stephen King's 1980 novella, The Mist. King's most Lovecraftian yarn, The Mist is about a fog that descends on the New England town of Bridgton. This white shroud hides giant spiders, tentacles, and other monsters in its folds. The horror comes from the potential that abominations of any proportion could be hiding feet in front of your face, and you wouldn't know it. However, in true King fashion, the other danger is what normal people will do to each other in times of desperation. Even the arrival of the fog is probably attributable to people. Close to Bridgton is a military base that purportedly housed a project called "Arrowhead". According to business owner Bill Giosti, the base was performing atomic experiments, which we can speculate ended in a resonance cascade of sorts.[5]

Head of Valve, Gabe Newell, had read The Mist before brainstorming for Half-Life. One title the studio considered for their game was "Quiver", a name that would link it back to The Arrowhead Project.[6] Half-Life and The Mist are both about other-worldly creatures invading Earth and feature the military prominently. Half-Life also has killer tentacles extending from unknown sources in the levels Blast Pit, Surface Tension, and Interloper.

And we can't forget that authorities tried to hide the red flags and then the active emergency at Chernobyl. Valery Legasov, the Chief Deputy Director of the Kurchatov Nuclear Energy Institute, says that when he cautioned operators about the defects in the RBMK reactors, he was ignored.[3] Immediately after the meltdown, the government also did not inform residents in the vicinity of the incident. Half-Life imports the attempted hushing of a crisis at a scientific facility and the physicist trying to slow a car crash already in motion.

Even with ardent competition, video games have come out on top as the medium that pledges the least critical fealty to the American military. To this day, so many huge games portray any soldier with old glory on their shoulder as a valourous good guy. While Half-Life never puts a name to its antagonist, it takes place in New Mexico; the military here are obviously American, and the game depicts them as capable of a war crime on home soil. In Western nations, Chernobylfrequentlyserves as a shorthand for perceived inefficiencies in Soviet and socialist systems, distinct from our economic and governmental apparatus. Yet, Half-Life imagines a disaster and toxic response of the same scale and severity being possible within the borders of the United States. It's a tributary of the Half-Life/Portal universe's distrust of institutional authority.

Select individuals who work for scientific organisations like Black Mesa might be commendable, but as entities, Black Mesa, Aperture Science, The Combine, none of these spectres are trustworthy, and the armed forces are just dogs. "We've Got Hostiles" introduces a mechanic it often invokes near enemy squads where we must duck under lasers, giving an oppressive effect. In the chapter Apprehension, a couple of Soldiers will throw Freeman, still alive, into a garbage crusher. This disbelief in enforced hierarchies may be related to Valve's famously flat studio structure. There are leads on projects, developers who occupy more senior social positions, and owners, but Valve doesn't believe in official bosses, and Half-Life is very wary of them.[7]

On A Rail

After Crowbar Collective's makeover, On A Rail is a whole new person. Valve's version of the chapter was a long march through successive military ambushes, and it made it feel impossible to escape the army. Crowbar's rendition is a dark, quiet reprieve from the surface world that turns the volume down so it can bring it back up blaring in Apprehension. It also provides a breather from constantly fighting Soldiers, something that you don't get in the original game. Half-Life 1 plays the human-heavy levels On A Rail and Apprehension back-to-back.

The anger that the deceptive and meandering level design of On A Rail inspires means you can look straight past its setpiece ending, which was remarkably well-received by players. If you saw the rocket in Black Mesa Inbound and thought, "It would be so cool to launch that", this mission has got you. We'll need the satellite it puts in orbit for later. Valve would later expand the rocket launch concept into a whole game with Half-Life 2: Episode Two.

Residue Processing

The level in which we discover how Black Mesa disposes of waste comes right after the Marines try to throw away Freeman, chucking his stunned body into a trash compactor. Residue Processing also begins some real game designer's game design. At the end of the previous chapter, the boys in camo repossessed all of your weapons, and you slowly regain them over the course of this and the coming missions. Where FPSs often start with melee implements and pistols, work up to automatic rifles, and then crescendo with rocket launchers and esoteric blasters, Half-Life can rewrite that order and force you to work around the gaps in your inventory.

This isn't possible from the start of the game as the designer needs to first hand you trivially operable guns and then graduate you to the more finicky tools. But by Chapter 9 of Half-Life, we are experienced with most weapons, and the designers can set out a new order for us to discover them in without bamboozling us. The game also has the weapon set reflect that we are getting closer to the alternate universe of Xen by giving us a couple of alien guns: The Snarks in Questionable Ethics and then the Hornet Gun in Surface Tension. From an aesthetic perspective, you can also see how the rusty tunnels and smashing pistons in Residue Processing were a dry run for the backstage areas of Portal. Tantalising.

Surface Tension, Forget About Freeman

With our arrival in Surface Tension, we are finally able to taste fresh air again. There are some beautiful New Mexico landscapes in this sequence. Just like a film can substitute one location for another, most of the reference imagery for Valve's New Mexico was actually taken in Eastern Washington.[6] Valve will revisit this style of rocky, remote setting in Team Fortress 2. Naturally, Black Mesa's version of this stage is more upfront about what we should and should not do to cross the desert. For one thing, the landmines are now visible and destructible; detonating them feels like popping bubble wrap.

The guard towers and booths you'd associate with a prison, and a desert that stretches all the way to the horizon, tell us that we cannot simply run from Black Mesa, and we've known for a long time now that the military isn't going to rescue us. We need a more permanent solution, especially because the aliens are catching up to the Soldiers in terms of the threat they pose. Xen's regiments have disabused us of the notion that they're atavistic animals and have increasingly proven themselves to be an organised intelligence. By Chapter 13, Forget About Freeman, the Marines are in retreat, and we're stuck in the compound with the monsters that beat the US military. But experimental scientists like Freeman are all about solving issues, and hope remains at the Lambda Complex.

Lambda Core

Perhaps if science is the problem, it can be the solution. The Lambda Complex houses a nuclear reactor, and if we can fire it up, we can use it to open a portal to Xen. There, we can plug the invasion at its source. So, we do that in the fourteenth level: Lambda Core. Valve would later release two whole games about portal technology set in this universe, with Portal 2 also ending with us opening a doorway to a celestial body. At one time, the studio intended Half-Life's opening level to be called The Portal Device.[8] Although, where Aperture Science has this white plastic Apple look, Black Mesa doesn't appear like anywhere that was meant to be shown to the public. With Lambda Core, Half-Life makes it clear that despite its Chernobyl parallel, it believes in the power of nuclear energy to positively transform our world. It's recklessness with the technology that is the folly, not the technology itself.

Xen

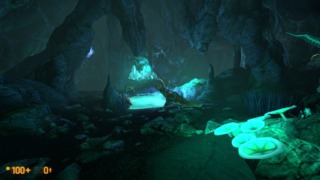

On the other side of the portal, Crowbar Collective surprises us. There have been films and TV shows that shock and delight audiences by deviating from the established events of an existing narrative, like Once Upon A Time in Hollywood or Scott Pilgrim Takes Off. Black Mesa is doing the same thing but for level design. Not only do they replace the Xen excursions with original missions, but they also extend Valve's architecture. It's a significant factor in How Long to Beat listing the Half-Life campaign at twelve hours long, but Black Mesa's at fifteen.

In the original Half-Life, Xen is a mulch of rock and meat, but in Black Mesa, we also brush past rainforest leaves and hear mock whale song. Valve's borderworld is disturbing because it's featureless, while Crowbar's has more than one personality but includes a thriving ecosystem. It avoids the naive view of nature. Some people and media think of life outside towns and cities as living in romantic harmony. Black Mesa establishes a more convincing ecosystem by giving us animals that can exist in equilibrium but are still ready to burn through prey with acid or bite their heads off. When you see the Headcrabs and Houndeyes in their natural environment, they immediately make sense.

The early outworld has none of the living scientists, guards, or recharge stations that we've come to rely on, making it audiovisually and mechanically inhuman, even if the 1998 hinterland is infinitely inferior to 2020's. Try to climb a hill in the original environment, and you'll get locked into a painfully slow slide up the terrain. For a programmer, it's relatively simple to calculate the movement of one flat object over another, and the research facility is flat ground. Even the parched desert of Surface Tension is mostly level. But the exoplanet of Xen is naturally going to be rocky, or where it's made of biological matter, lumpy, and calculating the interaction of a flat object and a curved object is a greater ask for a program, one that's beyond GoldSrc.

On Xen, all vaguely complex movement leaves me fumbling. The worst sections are those where you must jump from one slow-moving rock to another in low gravity. Games are almost always reliant on us having a basic understanding of how our tools work and what we're meant to do with them. At the start of Half-Life, I might not understand the nuances of all my guns or the enemy types, but I have a pretty good conception of how a bullet will move when I fire a gun and where I'm meant to aim. A decent platformer will give you a rough idea of your jump arc, where you need to leap from, and where you need to land.

In Half-Life's fifteenth mission, everything you learned about jump physics goes out the window. And as Xen demonstrates, the slower the objects involved in a physical interaction move, the further into the future you have to calculate outcomes. Our predictions are made harder by the first-person perspective; you can't see where exactly you stand in the context of the larger environment, and it's not uncommon that while you try to leap from pillar to post, enemies will take potshots at you. Once you are in the air, attempting to press the back key so you don't fly past the platform also disables further air control, reducing the amount you can finesse any jump.

Half-Life's controls are tuned for twitchy arena shooter combat. It wants you to be able to get up in another player's face in a couple of seconds. When you apply that same movement to a platformer section, it feels like trying to drive a Ferrari over stepping stones. And because you could send a letter to someone in the time it takes a platform to complete one cycle, a lot of my memories of these spires are of me standing around, waiting for platforms to line up. Xen's inadequacies are generally blamed on Valve rushing to finish development, but much better than rushing Xen would have been cutting it entirely.[6]

Gonarch's Lair, Nihilanth

In a more rational world, we could take comfort in the bunny hopping being only one tine of the platforming/combat/puzzle trident, but the Nihilanth, the game's final boss, can also teleport you to a tower of platforming terror. Just when you thought you got out, they pull you back in. It's tedious because it's more platforming, but it's also disruptive to the boss fight because the platforming doesn't integrate into the battle with the psychic fetus. It's an unrelated challenge in a different room with no Nihilanth in sight. This prestige is also eerily quiet; it's absent of music, and there aren't even many sound effects.

Black Mesa's Nihilanth shootout is, thankfully, 100% platforming-free, guaranteed. Yet, it still toys with Half-Life's interest in teleportation technology by having chunks of the facility arrive in the mastermind's nest. Black Mesa has a refreshingly narrative philosophy about boss fights. The game does not end with the most strenuous combat: that would be the Gonarch boss fight. The villain of an entire level is made into an on-again, off-again encounter. The Gonarch is not just sublime in its goring charges but also its unfettered reproduction. The Nihilanth battle, by contrast, sends the game off on its most extravagant note.

Black Mesa further patches Xen's surface interaction and makes platforming more straightforward by removing crouch jumping and implementing intuitive double-jump controls. It normalises your speed, and when it does have you boost yourself to a distant surface, it ensures it's stationary and sizeable or backed by a wall. You won't overshoot as long as you're reasonably sharp at platforming. Crowbar's skyboxes for Xen should hang in a museum, and on this land, the developer awards us more of the tastiest enemy dynamic: that between the Vortigaunts and Alien Controllers.

Interloper

On Xen, Vortigaunts are pacifists when left to their own devices but will rain hell down on Freeman when a nearby Alien Controller connects to their cortex. The Controllers make for slight targets and can maintain command in a battle even from a distance, but they are nothing without their guards. As the dance with these dime-store Modoks is a constant motion, you have to keep asking, is it more practical to take out multiple immediate targets (the Vortigaunts) or try your hand aiming at distant glimmers (the Controllers)? And there is the ethical dimension. Could you stand to kill the Vortigaunts when they're powerless slaves? And what more perfect relationship is there than foreman and engineer for the sweaty manufacturing and packing plant of Interloper? The drudgery of the Vortigaunts speaks to the game's themes of industry run amok and man against institution.

Unfortunately, Crowbar accidentally made too much Interloper. I know what you're thinking: "A boring amount of time spent in the box factory? There's no such thing", but the level machine broke down, and now conveyor belt platforming sections won't stop coming out. It's an unlikely blemish on a game that was made by a small, formerly amateur team that is otherwise discerning when pruning Half-Life's dead leaves.

A Battle You Have No Chance of Winning

Endings are hard. Most writers want to cap off their stories with the protagonist seeing their every wish granted. This approach to plotting can be disappointing in its predictability. Half-Life's ending reignites our interest in the narrative by letting us see past the battle we've fought for the last twelve hours. It all revolves around the G-Man, a besuited figure with bleached skin and uneven speech who knows all too much about the events of the game. While "G-Man" has become the accepted name of the character among fans, he's too cryptic for the developers to give him any canonical label. The name "G-Man" was pulled from the program files, but we generally don't take metadata as an authority on the canon. There's a model titled "scientist01" on the disc, but we wouldn't surmise from that that the character it depicts is called "Scientist 01".

But we need some words to refer to the man with the briefcase, so I'll keep calling him "The G-Man". The G-Man gives Gordon a choice that's not really a choice. He considers Gordon's sealing of the portal to Xen to be an audition, one that he's passed. The G-Man tells us we can either accept a mercenary contract with his employers or die. More than a decade before avant-garde subversions like The Path, Half-Life laid out this interactive thesis that a choice where one of your options is failure is no choice at all. Our negotiation with The G-Man takes place in the same model of tram that we rode into the facility on, but flying through a field of stars. The coding is that Gordon is once again going through a transition and heading to a site of conflict.

Here, players may find pieces of the story that previously seemed free-floating coming together. We know that Black Mesa researchers made expeditions into Xen, and in Black Mesa (the game), their presence there is pronounced, with makeshift encampments full of whiteboards, as well as Headcrabbed scientists. In Chapter 11, Questionable Ethics, we explored a lab where aliens from Xen were subject to cruel experiments which fruited in face-melting lasers. So, while the accident at Black Mesa was down to human error, it didn't come out of the blue. Just like the military in The Arrowhead Project and the Soviets at Chernobyl, Black Mesa, or its unseen administrators, had been playing with fire for a while. While the devils of Xen deserve no peace prizes, what happened in the New Mexico desert was not a freak invasion; it was a counteroffensive.

It may even be that someone intentionally sparked the resonance cascade. During Anomalous Materials, nosy explorers will have seen the G-Man opening a briefcase and showing the Black Mesa scientists the sample Gordon placed in the anti-mass spectrometer. Whether the G-Man's employer was the US government, we don't know, but the game leaves open the possibility that it was. As we see in Black Mesa Inbound, there's a USMC presence in the facility, and in the space tram, that creep tells us some of our weapons are government property, but is the government property just the guns we scavenged from the military or also the devices developed at Black Mesa? And here's some more food for thought: Gordon Freeman's sponsor in Black Mesa is classified; someone or some entity mysterious and important. Could it be the G-Man or the people he works for?

At the end of Half-Life and Black Mesa, there is a feeling of having travelled a great distance because of a lack of cutscenes that teleport us from one place to another. Everywhere Gordon went, we went. Additionally, Valve posits a lot of thought-provoking questions about their world without leaving out a sense of conclusion. Although, like Gordon, the Valve of this time had no idea how much further the G-Man would take them.

Departure

Half-Life is a lesson in how settings can be made to feel more realistic when the creator thinks of them as a working mechanism. It's a classic example of the mechanical theming of areas providing them with distinction and character. It's an argument for the atmospheric power of setting your media in the aftermath of a disaster. It's also proof of how you can use escalating revelations to keep the player on the edge of their seat until the last minute.

And what do we make of Black Mesa, a game that aims to court the Half-Life fan, even while rejecting much of its material? How can it be a celebration of the advancements I mentioned when it assesses Valve's work with an eraser in hand? Black Mesa says that homage takes a little criticism. If you believe in a piece of media, then you know that it can stand up to scrutiny, that it won't fold at the first sign of scepticism. And if that work helped modernise its format in its time, then celebrating it means striving for a comparable contemporaneity.

We can get so sensitive about the literal accuracy of video game remakes that we don't allow them to convey what was special about their source material. If you want a version of a game where the original gameplay is preserved, but the visuals are overhauled, I have no problem with that. More power to you. But if what we're searching for is the preservation of a game's spirit rather than its literal code, a redesign rather than a republishing can show you who the game truly is. Black Mesa is the poster child of that philosophy. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- The single cutscene in the game consists of Soldiers carrying your body towards the crusher at the end of Apprehension.

- Chernobyl Accident 1986 (April, 2024), World Nuclear Association.

- Rich, V. (1988). Legasov's indictment of Chernobyl management (Content Warning: Suicide). Nature vol. 333 (p. 285).

- Decay Constant (January 19, 2024), Britannica.

- King, S. (2007). The Mist. Signet Book (p. 31-32).

- Half-Life: 25th Anniversary Documentary by Secret Tape (November 17, 2023), YouTube.

- What's It Really like Working at Valve? We Found Out. by People Make Games (January 25, 2023), YouTube.

- This is evidenced by the Half-Life pre-release build that leaked in 2013.

All other sources linked at relevant points in the article.

Log in to comment