Yussef Cole is a writer and motion graphic designer living in the Bronx, New York. He is a regular columnist at Unwinnable, and design director for Netflix's Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj.

He writes primarily about how video games intersect with broader cultural contexts such as class and race. His writing stems from an appreciation of the medium tied with a desire to tear it all down so that something better might be built.

He's @youmeyou on Twitter.

Mutazione

When so many games seem committed to guiding you towards the fastest, most efficient approach--the quick-load, the insta-click respawn into the dropzone--it’s refreshing to play a game like Mutazione which is happy to let you take your time exploring geographical and narrative axes, and forge strong connections along both. It’s a game where, at some point in each in-game day, your character gets tired and just has to go to bed, no matter how big the mystery they’re pursuing may be. It’s a setting where the various inhabitants come off as welcoming and chatty at certain times, and exhausted and aloof at others. In this way they feel more grounded and alive than the cardboard quest givers which sloppily encapsulate humanity in other games.

Mutazione tells a humble story, one where all the world shifting events have already happened. The set pieces you come across aren’t meteor impacts or sweeping wildfires, but people with buried tragedies and traumas. In some ways just as momentous, if far more subtle and potentially rewarding to navigate.

Observation

Despite the lack of a playable human protagonist, Observation does not feel like a departure. Games, after all, are mostly observation. Sure, you’re usually controlling a named character who’s ostensibly interacting with the world around them. But more often than not that character is a silent cypher without an explicit identity or a stake in the outcomes, a superhuman who cannot die, a shining sun around whom the events of the game casually revolve.

Observation sidesteps this artifice by wholly embracing artifice: you are bodiless, or rather, your body is the entire game. You are a space station A.I. embedded in the structure of a station which has wandered thousands of miles off course. There are humans in the game and, like other games about haunted derelicts in space, you spend most of your time trying to solve these humans’ problems. But it feels so much more honest to be doing so as cold code and machinery than as something pretending to be flesh and blood. You’re putting out fires because they’re blights on your own physicality, not because you’re an engineer who’s somehow also combat-trained. The game pulls off a feat, putting life into the unliving, putting the emotion of you, the player, into something which is supposed to be emotionless; questioning, as a result, the assumption that emotionlessness is truly the ideal state for the machines which serve us (and if servitude is as well).

Fire Emblem: Three Houses

Fire Emblem is a game for those who wonder what their soldiers think about in the countless moments which exist before and after they are ordered to attack and murder someone else. It’s a hundred hour exploration of that interaction that happens in the old Warcraft games, when you repeatedly click on a knight until he idly complains about life in the army and his desire to go sailing.

But unlike with the Warcraft unit, who has no notion of what unseen force is guiding his movements, the student soldiers of Fire Emblem have a strong connection to you, their teacher and master. And over the course of the game, it’s hard not to develop a strong connection to them. This is carried out through events such as tea parties where you can complement the embroidery of a student’s collar and ask probing questions about their personality. It might also happen over a shared meal, something you selected knowing full well that it’s their favorite dish. You can buy your students flowers and toys and answer their adolescent and querulous concerns. This relationship grind serves to add depth to the many battles which punctuate your school sessions, but it also winds up making the battles feel tonally wrong: something so black and white as ending a life shouldn’t be carried out by such complex and multi-faceted beings. Unfortunately the game has little more to ask of you, the player, other than to nurture these lost souls’ wounded hearts as they return from battle, only to send them out again after a few more shared meals and tea parties.

Resident Evil 2

Playing Resident Evil 2 feels like being stuck in a baroque doll house with a big angry baby, like a trench coated version of that baby Boh from Spirited Away, smashing his way through walls and doorways and flailing in your direction as you desperately try to stick a heart shaped key into a diamond shaped hole. It’s stressful and terrible and also incredibly fun. Like any good horror story, Resident Evil 2 finds ways to keep the tension at a high, nearly unbearable level. It does this by placing increasingly elaborate and challenging obstacles in your path. First, shambling zombies that still manage to effortlessly juke your head shots and deplete your ludicrously small pistol clips; then, menacing lickers who cling to walls and sniff at the air as you pass within a hair’s breadth; finally Mr. X himself, who adds a layer of panic and recklessness that compounds the threat posed by all of the previous enemy types. Like I said: stressful and terrible and also incredibly fun.

Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice

The joy of Sekiro is entirely inseparable from its frustration. The shuddering clang as blade edges slide off of each other is also the split-second kernel which contains everything else in the game that matters. It’s about learning to become the idealized version of your character, learning to effortlessly bound through levels with a full health bar and plenty of extra lives as you reflect deadly blows without pausing or looking back. Less Ockham's razors, more blunt butter knives; less mortal coils more, immortal tangents. Sure, the game still tells a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of pride and bravado. It wouldn’t be a good Souls game if it didn’t. But it can only pull this off by first dangling in front of the player the prospect of perfection, of transcendence: of no-hit runs, of slow-mo finishers, the preening stuff that video game hubris is built from. This mess of contradictions is what makes Sekiro so sticky, and so very exciting to play and think about.

Pathologic 2

Pathologic 2 is poetry snuck within the garb of prose. Its story and characters stretch along the expanse of a medium-sized town and twelve deceptively long days, but it’s also full of small, sharp moments. Gathering herbs in the shadow of a mountain sized slaughterhouse. Collecting water bottles which can be filled with either blood or water. Stumbling around plague infested homes, trying not to fall within the clouds of cursed miasma left behind by the dead. The game speaks in metaphor. The whole geography is metaphor: it’s a town, a living animal, a mortuary, a collective dream, a theatrical production. It’s society too, the one we live in and where we load the game onto our computers. It’s the rich protecting themselves from the poor, and the poor tearing at each other in a desperate bid for survival as the environment chokes and swallows them up. Pathologic 2’s poetic vignettes are sharp and leave painful recollections, but the prose spelled out by its length leaves a more lasting and thoughtful impression, a weight that stays with you long after you move on and attempt to go back to living.

A Plague Tale: Innocence

A Plague Tale covers similar ground to Pathologic 2, but within a lighter, more digestible package, one which follows the well-trodden path cleared long ago by games like Uncharted. Set pieces and richly dressed environments tell its story, and simplistic puzzles provide enough gamey tension to justify the player’s involvement. This functional simplicity aside, Plague Tale does a superb job of telling the story of a society that was sick long before disease hit. Plagues and pestilences historically reveal inequalities lying dormant within the structures of the sites they infect. Back in the 19th century, London’s Parliament held off on implementing a sewage system until the raw smell of human excrement from the neighboring Thames wafted up directly through their windows. In A Plague Tale, the religious order of the day intends to use the sickness carried by the ubiquitous rats to further their own ends. For normal people and the poor, vulnerable as the rich are not, all that can be done is to hide from the onslaught, or perhaps as this game suggests, to smash holes in the barricades and let some of the darkness back into the seemingly impermeable fastnesses of wealth and power.

Bleak Sword

There’s a feeling both instantly familiar and comforting that comes with playing a game like Bleak Sword, in spite of how outwardly unfriendly it makes itself out to be. Crunchy pixels, moody gothic spaces, and short, deadly battles play predictably like the greatest hits of the very good lineage inspired by the Castlevania games and the Berserk mangas. What’s new here is the interpolating factor of the phone screen, which, though often a hindrance to many other games, feels like a fitting canvas for Bleak Sword’s near-flat diorama-like arenas. The limitations of the touch screen are smartly used to reduce the level of input down to whatever is needed to drive instantaneous reaction. The shape of the arenas result in a flattening of depth which muddies player perception and makes it difficult to properly judge the proximity of targets. This means you’re required to make calculated leaps and flail occasionally, or often, as you are swarmed by encroaching enemies cycling through their trickily timed attack animations. Playing the game feels both desperate and controlled at once; enormously vibrant and expressive despite being presented through so many limiting filters--more likely as a direct result of them.

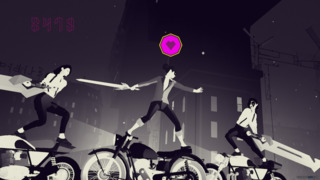

Sayonara Wild Hearts

Sayonara Wild Hearts is pure joy and cheeky as heck. It’s to games what dancing alone in front of the mirror to your favorite song is to high school: a splash of unironic pleasure in an otherwise cynical and joyless pond. Each level has plenty of challenges and points to gather, but the loose structure they provide feels subservient to the more immediate desire to maintain the effervescent mood established the moment the game boots up and plays the first note of its theme song (and you hear Queen Latifah’s echoing, silky voice). Sayonara Wild Hearts is a lightning bolt of confidence straight to your heart. Instead of battling against deadly adversaries you square up with sexy dancing partners. You break their hearts, but only in the mock flirtatious manner friends and lovers use to school each other on the dance floor: one-upping one another with displays of mutual agility and grace as a way to ultimately boost each other’s self-confidence and pleasure. It’s hard to come away from a the session of Wild Hearts without a big stupid grin on your face, all dipped in elation. And that, in this shitty year of all years, is accomplishment enough.

Neo Cab

Neo Cab is a haunting game. It curses your phone long after you’ve closed it and opened up the Uber or Lyft app to request a ride, Seamless to order a meal, or Fiverr to have someone come clean your house. It haunts us because it maps so cleanly onto the transactional nature of our contemporary first-world lives; the weird boundaries we decide to obey or dispute that are nonetheless there, often erected against our will by the digital paymasters who control how we live our lives.

Neo Cab has you playing as a woman named Lina driving for the eponymously named app. Her journey is one of navigating externally enforced boundaries enacted by massive corporate forces while trying, and often failing, to protect her own. It’s about her vulnerability in the cab, with no bulletproof divider between her and her fares, and the messy combination of human interaction alongside economic necessity that this openness encourages. Standing up for herself to a belligerent fare means losing stars off her rating, means staying out late to play catch up, means crashing at a pod hotel owned by the same company that’s trying to put her out of business. She is shunted from poor choice to poor choice, but she does have some measure of power: her empathy and her ability to connect with other people thrust into her life through these same mechanisms. This is perhaps the clearest message Neo Cab has for us: even as we feel isolated and funneled down one path or another by uncaring corporations, our ability to connect to one another and to tell each other our stories means the boot on our necks will never find permanent purchase, and the spark of life will always remain smoldering somewhere to threaten the spotless neon systems which strive so hard to snuff it out.