On a recent episode of the morning show, people jumped on me about a comment related to MachineGames' Wolfenstein: The New Order. I remarked that yet another Wolfenstein game in 2014, a series that has been kicking around in various forms of quality since the early 1990s, was a bit depressing.

The comment was spurred by a tweet making the rounds:

Moore's Law: Wolfenstein game graphics, 1992 vs 2014 pic.twitter.com/i6VADaIn0G

— Vala Afshar (@ValaAfshar) May 31, 2014

Some context. I said this after an hour with Wolfenstein, and I've since finished the game. It's terrific, comes highly recommended, and Alex's review nailed it. The New Order is a game comfortable dancing between schlock and tenderness, perhaps the most surprising comment ever about a game in which you fight Nazis with a space base. That Wolfenstein is more than merely a quality new first-person-shooter with the Wolfenstein name on the box should come as little suprise, given this team's pedigree. Many of the developers at MachineGames came from Starbreeze, the studio responsible for The Chronicles of Riddick and The Darkness. (Starbreeze still exists, making great games like Brothers.)

Clearly, these folks have a knack for wonderfully creative work within the confines of an already defined universe. In the case of all three, though, they were mucking around in playgrounds with serious freedoms. None were, say, strict film adaptations.

In an interview with Polygon, creative director Jen Matthies explained how MachineGames actually landed the Wolfenstein gig:

"The first thing we did was just brainstorm many different game concepts," says Matthies. "And then we went around pitching those to various publishers. That was basically the first year and a half."

Those game pitches were all strikeouts. The same year, ZeniMax Media announced it had acquired id Software--and all of its IP, including Doom, Quake and, of course, Wolfenstein.

Machine had pitched Bethesda on a game concept, but that game deal never came together. Bethesda suggested instead that maybe instead Machine might want to work on an IP from id's closet.

'Is anyone working on Wolfenstein?'" Matthies remembers asking. "They said, 'No, nobody's doing that.' We asked politely if we could have it."

I have no reason to believe this isn't true, and MachineGames was absolutely excited to work on a new Wolfenstein. On some level, it still irks me. I'd love to know what else MachineGames pitched. I know what bums me out--the perpetuation of old franchises due to market viability--but I'm less clear on the why, especially when MachineGames and Starbreeze have proven, over and over, that it's possible to do great things within existing ideas. It's an anomaly, but still: it exists.

And Wolfenstein is unique. It doesn't have the trappings of other long-running franchises, series that cannot easily deviate without inviting scorn from fans. It's the contradiction of creation: people say they want something new, but they'll keep buying repackaged old stuff. If we boil Wolfenstein down to its essence, it's about fighting Nazis as B.J. Blazkowicz. That's it. Everything else is wide open. So while, on its face, the idea of yet another Wolfenstein would seem to induce snores, that's actually a rather broad mandate.

What got me thinking about Wolfenstein was a reader pointing out a rhetorical contradiction of mine, thanks to the release of Gareth Edwards' Godzilla. I've been anticipating Godzilla since Edwards was assigned the project, even though Godzilla has been through the movie machine over and over again. There have been dozens of Godzilla movies since the kaiju's debut in 1954, and only a handful could be considered legitimately good. That sounds in line with how most longtime game franchises seem to go.

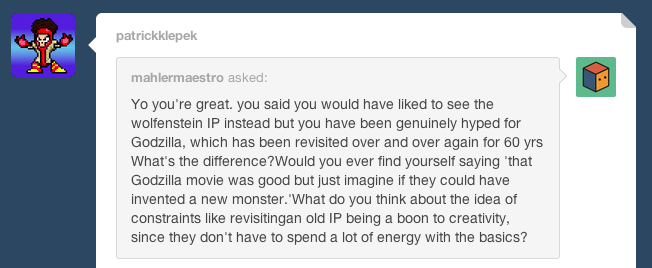

Here's what a reader asked:

Insofar as Godzilla movies go, there’s some nuance. Starting with the second Godzilla movie, the mostly abysmal Godzilla Raids Again, the pursuit of money transformed the concept of Godzilla. (Did you know the Americanized version of Godzilla Raids Again was called Gigantis, the Fire Monster, and they tried to pretend Godzilla (aka Gigantis) was a new creature?!) When considering Godzilla, most people remember the cheesy clashes the creature's had with other monsters. But the original film, called Gojira in Japan, is a mediated response to the devastation Japan experienced as a result of the atom bomb in World War II. Godzilla’s crumbled exterior was modeled after the skin of radiation victims. In Gojira, this creature is a walking nuke, a walking and fire breathing reminder of how crippled Japan was after the bombings.

With a few exceptions (i.e. Godzilla vs. Mothra, Godzilla vs. The Smog Monster), the series never seriously tried to reflect on society and culture again. The recent Godzilla tries to channel the terror of Gojira, though I don’t think “messing with nature” prompted quite the same level of emotional dread. But due to aging effects, it’s hard to recall the ol' rubber suit Godzilla was seen as a horror movie when it was first released.

Part of what makes Godzilla and Wolfenstein so attractive is how mired in genre they are. You might not expect social commentary from them, and that's exactly why they're such excellent vehicles for it. People tend to be more receptive to ideas when they're embedded within something that feels comfortable. In Wolfenstein, you have a game about stomping around in robots embedded with human brains that just might feature the most diverse casts of characters--race, gender, ableness--in a big budget video game. Hell, it even gets video game sex right--it's not just an achievement to be unlocked because you talked to someone enough. Blazkowicz might be grumbling busted one liners about kicking Nazi ass half the time, but the other half he's surprisingly eloquent about the human condition.

There's tonal commonality between the two franchises: the concept of a seemingly unstoppable, malevolent force we can barely comprehend. We return to stories like Wolfenstein and Godzilla because their cores remain attractive, even in 2014. Good vs. evil. Man vs. nature. We'll always want to kill Nazis and save the world, we'll always be frightened by a gigantic creature we cannot stop. It strikes at a core fear: the destruction of normality. It's what creators do with these stories that matters. Truth be told, I'll probably remain cynical when yet another franchise is brought out of the dust bin yet again. Not every developer is MachineGames. But more should learn from them.