It's hard to imagine how someone follows up Resident Evil 4, possibly the most influential game of the last decade. You can see pieces of RE4 in nearly every third-person action game produced after 2005. And that's forgetting Shinji Mikami is also responsible for the original Resident Evil, Vanquish, and countless others. For much of his career, Mikami's had the golden touch. The creator's latest comes with understandably high expectations, and while there are moments when The Evil Within rises to the occasion, it's a deeply flawed experience that's more prone to generating frustration than fun 'n scares.

The Evil Within opens with detectives Sebastian Castellanos, Julie Kidman, and Joseph Oda headed to a gruesome scene at Beacon Mental Hospital. Mutilated bodies litter the lobby, and it's unclear who's responsible. Castellanos discovers a supernatural presence with the ability to zip around the room at lightning speeds, and the trio's backup is quickly dispatched. All three are pulled into a hellish, everchanging nightmare under the control of a hooded man named Ruvik. Everyone around them has turned into zombie-like creatures with a penchant for murder, and thus begins a journey to figure out what the hell is going on. Spoiler alert: it gets really weird.

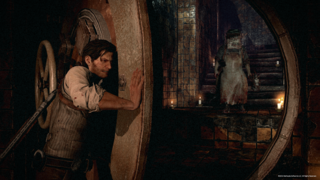

When The Evil Within was first unveiled, it looked as though Mikami was simply picking up where he left off with RE4, and the comparison holds up pretty well. Think of The Evil Within as RE4 with a serious stealth component and you're mostly there. Players guide Castellanos from a third-person perspective, often with a gun drawn and a lamp bobbing nearby, skulking around environments filled with dangers. Ammunition is scarce from start to finish, making The Evil Within one of the first games to live up to the survival horror moniker in a long time. This means confrontation isn't always the preferred route. Stealth kills are one-hit affairs, and it's possible to light various objects on fire with matches to take out nearby threats, as well. Taking advantage of these and other opportunities is crucial to moving forward. You cannot shoot everything in the head here. You'll occasionally team up with Kidman and Oda in scenarios eerily reminiscent of Resident Evil 5, but those moments are few and far between. Castellanos is on his own.

While the game stumbles out of the gate with a series of poorly structured tutorials, it settles into a familiar pace a few hours in. It's not a good sign when a game requires hours of patience before it's worth playing, but The Evil Within turns around. In yet another nod to RE4, Castellanos comes across a quiet village that's--surprise!--hiding a bunch of enemies. This section shows The Evil Within at its best, even if it's a high point the game reaches only a few other times. It's an enormous, layered environment with ample opportunities to experiment with everything available to players: stealth, traps, guns, running, hiding, etc. There's room for failure here, but there's always a sense of danger that keeps you tense. Key to success in The Evil Within is planning, execution, and improvisation. Since you're trying to conserve ammunition, manipulating stealth and traps is essential, but an enemy might make an unexpected turn. Or another enemy shows up. Or you set off another trap. There are countless reasons a plan implodes, but The Evil Within's combat is versatile in these open environments, and players can devise new approaches.

There are times when The Evil Within derives intense anxiety from the opposite scenario, too. One harrowing sequence involves navigating a simple series of rooms and hallways with invisible enemies stalking you in the dark. A chair will get knocked across the room, announcing an enemy presence, but other than a Predator-like shimmer, little else reveals what's out to get you. It still gives me the creeps.

How you approach an encounter can vary wildly, thanks to a welcomed variety in weaponry. Of course, there's the standard pistol, shotgun, and sniper rifle, but the agony bow is what's unique here. The agony bow can hold many different types of ammunition, so it changes functions on a dime. This includes bolts to send enemies flying, flash bombs to blind everyone around you (allowing for one-hit stealth kills mid-fight), freeze arrows with the ability to ice anyone within a few feet, and mines that can be placed anywhere in the world. More arrows become available as the game continues, and players both collect ammunition scattered throughout the environment and build their own by dismantling the many traps around them.

There are a handful of sequences when The Evil Within really clicks, the result of a designer strategically deploying his chess pieces, reflecting decades of experience. But the pacing of The Evil Within is relentless, and the creativity can't keep up. The moment you've cleared one room of enemies, there's another set around the corner. Always. Not all encounters are created equal, and this becomes more and more apparent as you progress. Rather than finding new scenarios in which you must develop new strategies, The Evil Within deploys more of the same with enemies requiring more bullets, creatures who can take you out in a single strike, and an endless array of boss battles meant to crush your soul.

Oh, lord, the boss battles. The Evil Within peaks early with a chainsaw-wielding maniac a la RE4 (notice a trend?), and with rare exceptions, nothing else ever comes close. What makes the chainsaw sequence work is his methodical pursuit. He lumbers forward in a way that gives you plenty of time to line up a shot, but it's not long before he's close, and you're forced to scramble away. (The other highlight, involving a dude with a safe for a head, works the same way). The Evil Within's other bosses largely involve bullet sponges capable of killing you after a single mistake. Whereas the rest of The Evil Within rewards planning, execution, and improvisation, the boss battles are little more than pumping a dog/lizard/whatever full of bullets. Castellanos isn't particularly nimble, which works just fine, since the enemies he faces aren't, either. But the bosses are capable of much more, creatures regularly lunging huge distances. It makes the battles especially frustrating, as the weighty character feels unfairly at odds with what's being asked.

Did I mention you face several bosses multiple times? Did I mention the game decided to bring some of them out three times, as part of a boss endurance run at the very end? The bizarre design logic is capped off by an on-rails final boss battle favoring spectacle, requiring little more than holding the fire button and waiting for the ending cutscene to kick in. It's a game that often can't help itself but indulge in every whim.

I watched The Evil Within's cutscenes, but couldn't say what happened. Mikami's games have always been campy, convoluted affairs, and The Evil Within is no different. But it's a waste of otherwise talented actors given very little to do. Apparently, Tango Gameworks hired Dexter's Jennifer Carpenter to show up for a day's worth of work, as she voices only a handful of lines throughout the whole game. (She does, however, have her own DLC coming later.) This underscores the muddled plotting more generally, a game whose A story--genetic tampering something something bad stuff oh wait there's monsters--is what's presented in the cutscenes, while the B story--a detective driven to alcoholism by the loss of his child and, eventually, wife--is only given lip service through awkward diaries.

It's probably worth noting the game's letterboxing at this point, too. The Evil Within's aspect ratio is 2.50:1, which translates to an extremely thick set of black bars at the top and bottom. While aesthetically unique, the game rarely leverages the aspect ratio to justify the amount of real-estate taken away from the player. Anytime you're asked to walk up or down a ladder, the bars become immensely frustrating. It's perhaps telling a recent patch for the PC version gives users the opportunity to flip them off entirely, providing evidence the bars have more to do with preserving technical performance than servicing a creative vision.

Speaking of the PC version, the game crashed nearly a dozen times during my 20 hours with it. Hmm.

It's hard for me to remember a recent game that provoked as much whiplash as The Evil Within. For every brilliant moment, there's a handful only worthy of exasperated annoyance. I haven't yelled at a TV screen and rage quit in a long time, but The Evil Within broke that streak. Congrats! I mean, we're talking about a game believing one of its last sequences, minutes before the game is over, should involve stealthing a series of spotlights. There are good ideas hiding in The Evil Within, but finding them just isn't worth it.